- Home

- Stuart Woods

Standup Guy (Stone Barrington)

Standup Guy (Stone Barrington) Read online

BOOKS BY STUART WOODS

FICTION

Doing Hard Time

Unintended Consequences†

Collateral Damage†

Severe Clear†

Unnatural Acts†

DC Dead†

Son of Stone†

Bel-Air Dead†

Lucid Intervals†

Strategic Moves†

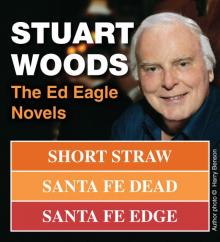

Santa Fe Edge§

Kisser†

Hothouse Orchid*

Loitering with Intent†

Mounting Fears‡

Hot Mahogany†

Santa Fe Dead§

Beverly Hills Dead

Shoot Him If He Runs†

Fresh Disasters†

Short Straw§

Dark Harbor†

Iron Orchid*

Two-Dollar Bill†

The Prince of Beverly Hills

Reckless Abandon†

Capital Crimes‡

Dirty Work†

Blood Orchid*

The Short Forever†

Orchid Blues*

Cold Paradise†

L.A. Dead†

The Run‡

Worst Fears Realized†

Orchid Beach*

Swimming to Catalina†

Dead in the Water†

Dirt†

Choke

Imperfect Strangers

Heat

Dead Eyes

L.A. Times

Santa Fe Rules§

New York Dead†

Palindrome

Grass Roots‡

White Cargo

Deep Lie‡

Under the Lake

Run Before the Wind‡

Chiefs‡

TRAVEL

A Romantic’s Guide to the Country Inns of Britain and Ireland (1979)

MEMOIR

Blue Water, Green Skipper

*A Holly Barker Novel

†A Stone Barrington Novel

‡A Will Lee Novel

§An Ed Eagle Novel

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

Publishers Since 1838

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA • Canada • UK • Ireland • Australia • New Zealand • India • South Africa • China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright © 2014 by Stuart Woods

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Woods, Stuart.

Standup guy / Stuart Woods.

p. cm.—(Stone Barrington ; 28)

ISBN 978-1-101-61588-1

1. Barrington, Stone (Fictitious character)—Fiction. 2. Private investigators—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3573.O642S73 2014 2013030289

813'.54—dc23

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

Contents

Books By Stuart Woods

Title Page

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

1

Stone Barrington made it from his bed to his desk by ten AM, after something of a struggle with jet lag. Granted, the three-hour time change between Los Angeles and New York was not a killer, but it mattered. As soon as he sat down his intercom buzzed.

“Yes?” he said to his secretary, Joan Robertson.

“You have a visitor,” she said, “name of John Fratelli. Says he’s a friend of Eduardo.”

“Send him in,” Stone said. Any friend of Eduardo Bianci’s was a friend of his.

A vision of the mid-to-late twentieth century appeared in the doorway.

“Mr. Barrington? May I come in?”

“Of course,” Stone said, rising to greet his visitor, who was wearing a boxy, light gray flannel suit, a starched white shirt, and what appeared to be a clip-on bow tie. He was carrying a salesman’s suitcase and a porkpie hat and had a haircut that had probably been accomplished entirely with electric clippers—short sides and a Brylcreemed top. “Come in and have a seat, Mr. Fratelli.”

“Thank you,” the man replied. “It’s nice of you to see me.” This was delivered in what appeared to be an old-fashioned Brooklyn accent, the likes of which had not been heard for many years from a man as young as Fratelli, who appeared to be no older than fifty. He came in and took the proffered chair across the desk and set down the suitcase.

“How may I help you?” Stone said, hoping the man was not a salesman.

Fratelli stood again, reached into a pocket, and pulled out a wad of bills; he peeled off five hundreds and placed them carefully on Stone’s desk.

“All right,” Stone said, “you’ve paid for a consultation and bought yourself some attorney-client confidentiality.”

“Good,” Fratelli said, sitting down again.

“I should inform you, though, that if you confess to a crime and I end up representing you in court, I will not be able to call you to the stand to testify on your own behalf.”

“Why not?” Fratelli inquired.

“Because I cannot call a witness to the stand who I know will lie under oath.”

“I understand,” Fratelli said. “That’s reasonable, I guess.”

“How is Mr. Bianci?” Stone asked, by way of getting the man to relax.

“Who?”

“Did you not tell my secretary that Eduardo had sent you to me?”

“Oh, I meant Eduardo Buono.”

�

�Not Bianci?”

“No, Buono.”

“I don’t know anyone by that name,” Stone said.

“Well, he knows you.”

“How does he know me?”

“He read an article about you in a magazine—Vanity Fair.”

That magazine had published an excerpt from a book about Stone’s late wife, Arrington. “I’m afraid I—”

“Eduardo says you’re a standup guy.”

“Well, as kind a characterization as that may be—”

“Eduardo and I shared a living space for twenty-two years.”

“I’m happy for you both, but that still doesn’t—”

“Eduardo was a very smart man, even if he did get caught.”

“Ahhhh,” Stone said. Now he understood. “Where did you do your time, Mr. Fratelli?”

“Sing Sing.”

“And when did you get out?”

“Yesterday afternoon.”

“How long were you away?”

“Twenty-five years, to the day. I did my whole sentence, no parole.”

“What was the rap?”

“Armed robbery. I did it, no excuses. That’s why I didn’t apply for parole.”

“Then you, not I, are the standup guy, Mr. Fratelli.”

Fratelli actually blushed. “Thank you,” he said softly.

“Now, please tell me, how can I help you?”

“Eduardo left me two million dollars,” he said. “And change.”

“Congratulations, but if you’re looking for investment advice, I’m not—”

“I’m looking for advice on how not to go back to prison,” Fratelli said.

“That’s fairly simple, Mr. Fratelli—don’t commit another crime.”

“Oh, sure, but—”

“Oh, I think I see. Did Mr. Buono acquire your inheritance by extralegal means?”

“Exactly.”

“Did he rob somebody?”

“Exactly, but Eduardo said the statue was done.”

That stopped Stone in his tracks for a moment, then he figured it out. “Do you mean the statute? The statute of limitations?”

“That’s it!”

“Well, the statute of limitations for robbery is five years, so if you and Mr. Buono were cellmates for twenty-two years . . .”

“So it’s mine, then?”

“I wouldn’t go as far as that,” Stone said. “It’s problematical.”

“I was afraid you’d say something like that.”

“Mr. Fratelli, let me put this hypothetically, since you and I do not want to discuss a real crime.”

“Okay, I get that.”

“If prisoner A committed a crime, and the statute of limitations has run out, then he can mention prisoner B in his will.”

“It wasn’t exactly like that,” Fratelli said. “There wasn’t—I mean, in this story prisoner A didn’t have a will, he had a safe-deposit box. He, hypothetically speaking, had a bank account, and every quarter for twenty-five years, the bank deducted the rental of the safe-deposit box from his account. From time to time, his lawyer deposited funds.”

“And prisoner B has access to the box?”

“Prisoner A told me—ah, him—where to find the key.”

“And has prisoner B visited the box?”

“You could say that.”

“And he emptied the box?”

“About an hour ago,” Fratelli said. “Just as soon as the bank opened, prisoner B was there with the key.”

“Did anyone see what he removed from the box?”

“No, he was in a little closet, and he had brought a suitcase. He just walked out with the money.”

“I see.”

“His question is, what’s he going to do with it?”

“Whatever he likes,” Stone said. “As long as no one knows he has it.”

“Does prisoner B have the money legally?”

“A better question might be, is anyone going to be looking for the money? A widow? A nephew? A bookie?”

“He didn’t have any of those, and nobody knows about the money. Hypothetically.”

“How about the lawyer who made the bank deposits?”

“He died three weeks ago.”

“Then, Mr. Fratelli, prisoner B is laughing.”

Fratelli laughed.

“His first move should be to go to a bank—a different bank—open a checking account with less than ten thousand dollars, then rent another safe-deposit box. After that, he could remove enough money periodically to support himself. Lashing out with large amounts could get him into trouble, as you might imagine. People will steal, after all.”

“Yes, they will,” Fratelli said.

“Ten thousand dollars is the magic number. If prisoner B banks that much, a form reporting it goes to the Internal Revenue Service, and, although they are said to have stacks of those forms, which they never read, it’s not a good idea to generate such a form. After all, they may start reading faster, or they may teach a computer how to read them.”

“That’s good advice,” Fratelli said.

“One other thing: if you should seek legal advice again, it might be in your interests to go to an attorney who has not heard this hypothetical story.”

Fratelli stood up. “Thank you, Mr. Barrington,” he said, offering his hand.

They shook, Fratelli left, and Stone opened a desk drawer and raked the little stack of hundreds into it.

Joan came in a moment later. “While you were talking to Mr. Fratelli, a secretary to the president of the United States called. You’re invited to dinner tomorrow evening with President and Mrs. Lee at their apartment in the Carlyle.”

Stone had not heard from the Lees in months. “Call back and say that I accept, with pleasure.”

“You may bring a date.”

Stone’s current squeeze, the fashion designer Emma Tweed, had returned to her native London for a few weeks. “Say that I will come alone.”

2

Stone wore a dark suit and a tie, because he didn’t know who else was invited. He entered the Carlyle Hotel and got off the elevator at the penthouse level, where he was greeted by two Secret Service agents to whom he identified himself. That wasn’t good enough; they went over him with the wand.

Katherine Rule Lee, now retired as director of Central Intelligence, answered the door. She was wearing tight jeans and a sweater, and she looked good in both. “Oh, Stone,” she said, offering both cheeks to be kissed and giving him a hug, “nobody told you to dress down?”

“I didn’t get that part of the message,” Stone said, “but I’m not in the least uncomfortable.”

“Will’s watching the news. Knob Creek?”

“Perfect.”

She pointed him at the living room, then went to the bar, while he continued.

Will Lee stood up and offered his hand. “Good to see you, Stone.”

“And you, Mr. President.”

“It’s still Will.”

“Good to see you, Will.”

The president waved him to a chair, and Kate brought him his drink.

“They’re showing excerpts from last night’s Democratic campaign debate,” Will said.

The three of them watched in silence until the program ended, then Will turned off the TV. “What did you think?” he asked Stone.

“I think there are at least three guys and one woman in that field who would make a good president.”

“And?”

“And not one who could win against Taft Duncan,” Stone said, referring to the Speaker of the House and presumptive Republican nominee.

“I’m afraid I agree,” Will said. “What have you been up to Stone?”

“I’ve just come back from Los Angeles, where my son, Peter, who recently graduated from Yale, has established himself on the Centurion Studios lot as a director. Dino’s son, Ben, is his partner, and Peter’s girlfriend, Hattie Patrick, writes the music for their films.”

“I’ve met them all, last ye

ar at the opening of The Arrington,” Will said. “Remember?”

“How could I forget?” Stone said.

They all shared a laugh.

“And what does the next year hold for you?”

“My year seems oddly empty, with Peter on the other side of the country, so I guess I’ll have to think about practicing some law. Bill Eggers is making broad hints about my absences from the firm.”

“Ah, yes, the partners won’t want to share income with one of their number who is an absentee.”

“Well, I have made a lot of rain,” Stone said, “so I don’t think I have to worry about them ganging up on me. What brings you to town?”

“Well, Kate is supposed to have an informal meeting with the board of Strategic Services tomorrow evening.”

“Yes, I know, I’ll be at the dinner.” Kate had been invited to join the board of directors after Will left office.

“Our other reason for being here is to see you,” Will said.

That puzzled Stone. “Oh?”

A man in a white jacket appeared and announced dinner, so they all went to a table with a spectacular view of the New York City skyline. Stone took a sip of his wine and waited for the president to finish his thought.

“Stone,” Will said, “the day before yesterday I received a bundle of twenty letters, each of them written by a Democratic Party bigwig or a major campaign contributor, all individually composed but with the same subject. Can you guess what that subject was?”

“Well, it seems a little late in the game to get a constitutional amendment passed that would allow you to run for a third term.”

“Thank God for that,” Will said. “What they wanted was what they see as the next best thing.” He sat silently and waited for the penny to drop.

It took Stone a moment. “Kate,” he said finally. “They want Kate to run.”

“Terrible idea, isn’t it?” Kate said. She had been quiet until now.

“I think it’s a terrific idea,” Stone said. “But we’re halfway through the primaries.”

“My very point,” Kate said, “but Will doesn’t think that is an impediment.”

“And I think Stone can figure out why,” Will said.

“Because it looks like none of the candidates is going to have anything like a majority of the delegates going into the first ballot at the convention.”

“Right you are.”

“So, for the first time in I-don’t-know-how-long, we’d have a brokered convention?”

“Since 1952,” Will said, “when Adlai Stevenson got the nomination. We’ve had some close brushes since, but not the real thing. The primary process usually works to nominate a candidate.”

Beverly Hills Dead

Beverly Hills Dead Shakeup

Shakeup Hush-Hush

Hush-Hush Wild Card

Wild Card A Delicate Touch

A Delicate Touch Dead Eyes

Dead Eyes Stealth

Stealth Loitering With Intent

Loitering With Intent Grass Roots

Grass Roots Scandalous Behavior

Scandalous Behavior L.A. Times

L.A. Times L.A. Dead

L.A. Dead Class Act

Class Act Dirty Work sb-9

Dirty Work sb-9 Bombshell

Bombshell Standup Guy

Standup Guy Quick & Dirty

Quick & Dirty Stuart Woods Holly Barker Collection

Stuart Woods Holly Barker Collection Standup Guy (Stone Barrington)

Standup Guy (Stone Barrington) Capital Crimes

Capital Crimes Kisser

Kisser Hot Pursuit

Hot Pursuit Choke

Choke Blue Water, Green Skipper: A Memoir of Sailing Alone Across the Atlantic

Blue Water, Green Skipper: A Memoir of Sailing Alone Across the Atlantic Under the Lake

Under the Lake Unnatural acts sb-23

Unnatural acts sb-23 Doing Hard Time

Doing Hard Time White Cargo

White Cargo The Prince of Beverly Hills

The Prince of Beverly Hills Severe Clear

Severe Clear Bel_Air Dead

Bel_Air Dead Severe Clear sb-24

Severe Clear sb-24 Unnatural Acts

Unnatural Acts Dirt

Dirt Foreign Affairs

Foreign Affairs Unbound

Unbound Family Jewels

Family Jewels Foreign Affairs (A Stone Barrington Novel)

Foreign Affairs (A Stone Barrington Novel) The Ed Eagle Novels

The Ed Eagle Novels Dirty Work

Dirty Work Fast and Loose

Fast and Loose Worst Fears Realized

Worst Fears Realized D.C. Dead

D.C. Dead Deep Lie

Deep Lie Santa Fe Edge

Santa Fe Edge Bel-Air dead sb-20

Bel-Air dead sb-20 The Short Forever

The Short Forever Run Before the Wind

Run Before the Wind Dark Harbor

Dark Harbor Shoot First (A Stone Barrington Novel)

Shoot First (A Stone Barrington Novel) Sex, Lies & Serious Money

Sex, Lies & Serious Money Santa Fe Dead 03

Santa Fe Dead 03 D.C. Dead sb-22

D.C. Dead sb-22 Swimming to Catalina

Swimming to Catalina Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage Hot Mahogany

Hot Mahogany Barely Legal

Barely Legal Imperfect Strangers

Imperfect Strangers Paris Match

Paris Match Mounting Fears

Mounting Fears Mounting Fears wl-7

Mounting Fears wl-7 Shoot Him If He Runs

Shoot Him If He Runs Short Straw

Short Straw Santa Fe Dead

Santa Fe Dead Dead in the Water

Dead in the Water Hothouse Orchid

Hothouse Orchid Below the Belt

Below the Belt Orchid Beach hb-1

Orchid Beach hb-1 Son of Stone sb-21

Son of Stone sb-21 Cold Paradise 07

Cold Paradise 07 Blood Orchid

Blood Orchid Fresh Disasters

Fresh Disasters Lucid Intervals

Lucid Intervals Dishonorable Intentions

Dishonorable Intentions Cut and Thrust

Cut and Thrust The Money Shot

The Money Shot Santa Fe Rules

Santa Fe Rules Iron Orchid

Iron Orchid New York Dead

New York Dead The Short Forever sb-8

The Short Forever sb-8 Son of Stone

Son of Stone Insatiable Appetites

Insatiable Appetites Chiefs

Chiefs Unintended Consequences

Unintended Consequences Reckless Abandon

Reckless Abandon Three Stone Barrington Adventures

Three Stone Barrington Adventures Stuart Woods 6 Stone Barrington Novels

Stuart Woods 6 Stone Barrington Novels Shoot First

Shoot First Indecent Exposure

Indecent Exposure The Run

The Run Bel-Air Dead

Bel-Air Dead Strategic Moves

Strategic Moves Cold Paradise

Cold Paradise