- Home

- Stuart Woods

Iron Orchid Page 11

Iron Orchid Read online

Page 11

“I’m retired from the dress business. My father had the business before me, and now my son is running it.”

The lights dimmed, and the curtain came up. La Boheme was beginning. In moments, Holly was entranced.

THE FIRST ACT WAS ENDING when Holly’s cell phone began vibrating. As the curtain came down she turned to Hy. “I’ve got to run ”to the ladies‘,“ she said, and she raced up the aisle ahead of the crowd.

She stood in a quiet corner of the lobby and opened the phone. “Yes?”

“It’s Ty, where are you?”

“I’m inside the Met.”

“You bought a ticket?”

“I got an invitation.”

“You got picked up?”

“Sort of. An elderly gentleman.”

“Is it Teddy?”

“I don’t think so,” she said drily. “Too old, too frail. He’s had a knee replacement. He’s wearing an obvious toupee, and I don’t think Teddy would be obvious. How did you do?”

“Nothing,” he said. “You want to get something to eat?”

“No, I’m enjoying the opera; I’ll see you tomorrow.”

“Okay, good night.”

“Good night.” She closed the phone, found the ladies’ room, then returned to her seat.

THE OPERA ENDED, and Holly was in tears. She hadn’t expected this. “Had you seen La Boheme before?” Hy asked, as they made their way up the aisle.

“No, I haven’t been to the opera before.”

“Were you waiting for someone?” he asked.

“Yes, a girlfriend; we were going to try to get last-minute seats, but she didn’t show, and you made me a better offer.”

“How about some dinner?” he asked.

“If you’ll forgive me, I’m pretty tired. I think I’d better get home.”

“Can I drop you?” They were outside now.

“No, it’s not far; I’ll walk.” That should ditch him, with his knee. “Thank you so much for the seat. I loved the opera, and I appreciate it very much.”

“Perhaps again next Friday night?”

“I’m afraid I’ll be in London by then.” He was sweet, but boring and way too old for her.

“Then I wish you a happy trip.”

“Thank you, goodbye.”

He turned and made his way down the steps toward the street, and she used the moment to check out the departing crowd. No Teddy.

Then, as she was turning to go, she saw Hyman Baum jogging toward the curb rather athletically, waving his cane at a taxi. He jumped in, and the cab drove away.

Holly was halfway home in her own cab before the penny dropped.

TWENTY-SIX

HOLLY FOUND LANCE the following morning in the twelfth-floor dining room having breakfast. “Good morning,” she said, “do you mind if I join you? There’s something I’d like to talk to you about.”

“Please sit down,” Lance said, handing her a menu. She gave the waitress her breakfast order, then turned back to Lance. She was very uncomfortable with this.

“How are you and Ty working out as partners?” he asked.

“I like him,” she said. “He’s bright and willing, even if he is a little stiff.”

“FBI men are often stiffs,” Lance said.

“The difference in our ages bothers me a little,” she said.

“Holly, I didn’t ask you to sleep with him.”

“That’s not what I mean. You see, we can’t work pretending to be a couple, and we don’t look like sister and younger brother, either; we just don’t look right together, and it complicates things a little.”

“I see your point, but I’m sure you’ll find ways around that. What did you want to talk to me about?”

Holly’s breakfast arrived, and she played with it a little, dreading what she had to say. “I think I might have met Teddy last night at the opera.”

Lance set down his coffee cup and stared at her. “You met him?”

“I was standing outside the Met, looking for Teddy, and this elderly man with a bad toupee and a cane walked up to me and asked if I’d like to be his guest for the opera.”

“Teddy’s supposed to be quite a makeup artist,” Lance said. “I should think that if he wanted hair, he’d make it look real.”

“That was my thought, too. He leaned on me going into the hall, said he’d had a knee replacement, and the recovery was taking longer than he’d thought. He said his name was Hyman Baum and he was a retired garment center businessman, a dress manufacturer. He said his father had had the firm before him, and his son had it now. He said he’d been going to the opera there since the sixties, and that’s why his seats were so good.”

“Where were the seats?”

“Row H, two and four.”

“That would take some doing at the Met; the best seats are held by long-time subscribers. What about him made you think he might be Teddy, and if you thought so, why didn’t you call for backup?”

“Once we were inside, it never crossed my mind that he might be Teddy, but after we left the building, after I’d declined dinner or a drink with him, I saw him running after a taxi, waving his cane.”

“Running after a taxi with a new knee replacement? I don’t think so.”

“Neither do I. But I didn’t think of that until ten minutes later, when I was on the way home in a cab.”

“Any idea which way his taxi went?”

“No, it could have gone anywhere-the East Side, the Village, the Bronx.”

“Describe him as accurately as you can,” Lance said, taking out a notebook.

“Blue eyes, close to six feet-I’m five-nine, and I was wearing three-inch heels, and we were eye to eye-fairly slender, maybe one-sixty; pale complexion, bags under his eyes, good teeth (too good for his age, maybe dentures, maybe prosthetic, part of the makeup); curved nose; fastidiously dressed but off-the-rack clothes, I think; liver spots on the back of his hands, and his hands looked strong. And, as I said, bad toupee: too low on the forehead, too thick, and the gray on top didn’t quite match the gray over his ears.”

“We could put you with a sketch artist, but I don’t think it would do us any good. If he wasn’t Teddy, it will just be a distraction; if he was, then the nose, the liver spots, the bags under the eyes could be makeup.”

“Maybe Hyman Baum is the identity he’s using; shall we cheek it out?”

“I’ll talk to Kerry and get some of his FBI agents on that; they’re more accustomed to background checks than we are. Did he say where he lived?”

“No, though he asked me.”

“What did you tell him?”

“I told him I was a widow, and I was staying with friends, before continuing to London. He also asked me to go to the opera with him the following week; he has seats every Friday night, apparently the same seats.”

“Well,” said Lance, “we’ll certainly be going to the opera next Friday night, and we’ll have seats H two and four surrounded. You were right to tell me about this, Holly. How did you do with the record store… what’s it called?”

“It’s called Aria, on East Forty-third.”

“That’s the one.”

“Ty went in, but I’m afraid the woman in charge reacted poorly to having an FBI agent in her store. I’m planning to go back and see what I can do with her.”

“See if you can soften Tyler up a little, will you? I’m afraid he’s the sort of young agent J. Edgar Hoover would have loved.”

“I’m trying.”

“Anything else you can remember about Mr. Baum?”

Holly thought hard. “That’s it, I think.” She felt humiliated and angry to have come so close to the man and to have let him walk so easily. She was beginning to really want him.

TWENTY-SEVEN

Teddy had worked hard on the new log-in codes for the CIA computers, but he had had to first log on as DDO Hugh English; it was unavoidable. Now, though, he once again had free rein to romp through the mainframe and the various servers and to

go from there into other government computers, state and federal, all over the country and in many places abroad.

It made him laugh. He could now register a car in Bulgaria or obtain an Idaho driver’s license; he could upload a Florida license to carry a concealed weapon, which worked in twenty-six states. Access to the Agency’s computers was a license to be anybody or to simply vanish into America. And nobody knew he could do it. He spent until early afternoon creating half a dozen new identities for himself, complete with credit reports, licenses and passports and uploading them into state and federal computers. Now he could enter the country or depart through any airport, and his I.D. would hold up.

After lunch he took a cab to the corner of Fifth Avenue and 43rd Street and walked down the block toward Aria. He was a few feet short of the shop when a woman got out of a cab and walked across the sidewalk to the shop’s front door, passing no more than six feet ahead of him. He felt a physical shock; it was the woman he had taken to the opera the night before-Holly something. He kept walking.

She had not so much as given him a glance, of course, since he looked very different today from last night. He crossed the street and stood behind a parked truck, trying not to tremble, watching the reflection of Aria’s shopfront in a store window. What was she doing in Aria? Had they somehow traced his interest in the shop? Of course, she liked the opera, or she wouldn’t have been there last night, but still, this was too much of a coincidence. He fought the urge to run, to go directly to the bus station and leave New York. But no, he had worked too hard to create this existence to simply walk away from it before he was sure how much trouble he was in.

HOLLY WALKED INTO ARIA and stopped when she saw the woman behind the counter. Ty had found her a tough nut to crack, and she looked just as tough now.

“May I help you?” the woman asked.

“Oh, I’d like to find a good recording on CD of La Boheme ” she said.

The woman got down off her stool and led her to a bin of CDs. “My favorite is the Pavarotti,” she said pleasantly. “Did you have a preference as to cast?”

“The Pavarotti sounds perfect,” Holly said. As she waited for the sale to be rung up she started to ask about anyone resembling Teddy, then thought better of it. She’d come back in a day or two and ask then. The woman might be more open if she recognized her as a previous customer.

“There you are,” the woman said, handing her a bag and her change. “Please come back.”

“I’d like to,” Holly said. “I went to see La Boheme last night at the Met. It was my first time at the opera, and I loved it.”

“We’ll always be happy to help you find recordings,” the woman said. “We have synopses and scores, too.”

“Thanks very much,” Holly said, smiling. She left the shop and walked toward Sixth Avenue.

TEN MINUTES LATER, the woman came out of the shop, and Teddy watched her back as she walked toward Sixth Avenue. Should he follow her or find out what she had done inside? Both, he decided. He ran across the street and walked into the shop. “Hi, Esmerelda,” he said to the clerk who was always behind the counter.

“Hi, there,” she replied, smiling at him.

“I thought I just saw someone I know just leave the shop. Was there a woman in here?”

“Yes, just a moment ago,” Esmerelda replied. “She bought a copy of the Pavarotti La Boheme. Said she’d seen the performance at the Met last night and loved it. Everybody loves La Boheme.”

“Did she ask about me?” Teddy asked.

“No.”

“Esmerelda, I have to ask you a favor. I knew her a couple of years ago. We had a relationship that ended badly, and since then she’s stalked me, done everything she can to make my life miserable. If she comes back and asks about me, I’d really appreciate it if you could deny all knowledge of me.”

“Sure, I can do that.”

“She might even send private detectives, and those guys use false I.D.s, say they’re cops.”

“Now that you mention it, a guy came in and flashed an FBI I.D., said he wanted to ask me some questions. I threw him out; I hate those guys.”

“You did the right thing,” Teddy said. He glanced at his wrist-watch. “Oh, my, I’m late for an appointment. I’ll have to come back.”

He left the shop and hurried toward Sixth Avenue. As he turned the corner, he saw the woman getting into a cab. He hailed another and got in. “Not to sound too dramatic,” he said to the driver, “but would you follow that cab, please?” He pointed to the taxi ahead.

“Sure, brother,” the cab driver said, sounding bored. “Whatever you want.”

“Not too closely,” Teddy said, “just keep it in sight.”

The cab made its way to an address in the East Forties, an apartment building. As Teddy waited in traffic, he saw her get out of the taxi and go into the building. The doorman touched his cap bill and opened the door for her. She was known there.

“Okay, now what?” the driver asked.

“Take me to Sixty-fourth and Madison, please.” He took out a notebook and jotted down the address of the building. What was the woman’s name? Holly something. He couldn’t remember the last name, though he tried all the way home.

Back in his apartment he went to the computer and logged onto the CIA server. What was her last name, dammit? He could check the Agency and FBI records for a file. He couldn’t think of the name.

Instead, he did a search for the address of the building she had gone into. The computer found three references to the address. He clicked on the first and found himself in a long, boring budget file. He checked the second reference. It was a memo: purchase of the building at that address was recommended, through a front real estate company.

He clicked on the third reference to the address and found a copy of a memo to the director from the head of purchasing, reporting on the appraisal of a building under construction and suggesting that it could be bought, approximately half-finished, for fifteen million dollars and finished to Agency specifications for another twenty million.

The building that the woman had entered was, at the very least, a CIA safe house, and, given the costs involved, more likely a center of some sort.

He slapped his forehead: he had sat through a performance of La Boheme next to a CIA officer.

“Jesus Christ,” he said under his breath. How had this happened? Were they that close to him? Impossible, he thought. If she’d realized who she was sitting with, she would have called in support, and yet she had let him walk. A coincidence? He hated coincidences.

TWENTY-EIGHT

HOLLY WAS CALLED into a meeting with Lance and Kerry Smith in the twelfth-floor conference room. Ty was there, and several other people who looked like FBI.

“Sit down, Holly,” Kerry said. “We’ve run a thorough check on your Hyman Baum character. There are several in the New York phone book, but none matching your description, and there is nobody recently in the garment industry by that name.”

“We think you’ve scored, Holly,” Lance said, “and I want to compliment you on your observation of this man. If he’s not Teddy Fay, then he’s someone else of the same description who goes around impersonating elderly dress manufacturers.”

Holly didn’t warm to the praise. “I didn’t score; I just stood there outside the opera and let him walk away. Or rather, run.”

“Don’t beat up on yourself,” Kerry said. “What’s important is that we now have a location and a target date for Teddy. We know he may be at the Metropolitan Opera next Friday night in seats H two or three. If he shows, then, for the first time since Maine, we’ve got a real shot at taking this guy off the street, and it’s all because of your good work.”

“Thank you,” Holly said.

“What we’ve got to do now is to formulate a plan for taking him in a crowded concert hall without anybody getting hurt,” Kerry said. “What I think we should do is put our people in seats all around him, and take him before the opera starts, the moment he sits

down.”

“I’m not sure that would work,” Holly said.

“Why not?”

“Because Teddy has these same seats every week, and so do all the people who’re sitting around him. If he walks in and sees a lot of strange faces around his seat, he’s going to bolt. I think it would be better to take him either as he enters the building or as he leaves.”

“You have a point,” Kerry admitted.

“Holly,” Lance said, “you met him outside the hall, right?”

“Right.”

“Well, then, let’s have you meet him at the same place again.”

“He invited me for next Friday night, but I told him I would be in London by then.”

“So, your plans changed, and you went back to the opera in the hope of being able to accept his invitation after all. At the very least, if he sees you, he’ll come over to ask why you aren’t in London.”

“It could work,” Holly said.

“We’ll arrange a visual signal: you’ll change your handbag from one shoulder to the other when you see him, and as soon as you start to talk, we’ll be all over him.”

“I’m game,” Holly said.

TEDDY CALLED Irene at home and had her walk out into her garden. “How are you?” she asked.

“I’m well. I got in with the new codes, but I had to log in as Hugh English the first time.”

“I thought that might happen,” she replied.

“If anybody notices, can you tell them that you logged on using his codes, just to be sure they were working?”

“Yes, I can do that; it might work.”

“Let’s hope nobody notices. Do you know a CIA officer based in New York with the first name of Holly?”

“No, I don’t, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t one.”

“I sat next to this woman at the opera, and later, when I saw her on the street, I followed her to an address on the East Side.” He gave her the address. “Does that ring a bell?”

“Yes, it’s a new, joint CIA-FBI counterintelligence operations center. If she got past the doorman, it’s because she’s authorized to enter. Do you have a last name for the woman? I can check her out.”

Beverly Hills Dead

Beverly Hills Dead Shakeup

Shakeup Hush-Hush

Hush-Hush Wild Card

Wild Card A Delicate Touch

A Delicate Touch Dead Eyes

Dead Eyes Stealth

Stealth Loitering With Intent

Loitering With Intent Grass Roots

Grass Roots Scandalous Behavior

Scandalous Behavior L.A. Times

L.A. Times L.A. Dead

L.A. Dead Class Act

Class Act Dirty Work sb-9

Dirty Work sb-9 Bombshell

Bombshell Standup Guy

Standup Guy Quick & Dirty

Quick & Dirty Stuart Woods Holly Barker Collection

Stuart Woods Holly Barker Collection Standup Guy (Stone Barrington)

Standup Guy (Stone Barrington) Capital Crimes

Capital Crimes Kisser

Kisser Hot Pursuit

Hot Pursuit Choke

Choke Blue Water, Green Skipper: A Memoir of Sailing Alone Across the Atlantic

Blue Water, Green Skipper: A Memoir of Sailing Alone Across the Atlantic Under the Lake

Under the Lake Unnatural acts sb-23

Unnatural acts sb-23 Doing Hard Time

Doing Hard Time White Cargo

White Cargo The Prince of Beverly Hills

The Prince of Beverly Hills Severe Clear

Severe Clear Bel_Air Dead

Bel_Air Dead Severe Clear sb-24

Severe Clear sb-24 Unnatural Acts

Unnatural Acts Dirt

Dirt Foreign Affairs

Foreign Affairs Unbound

Unbound Family Jewels

Family Jewels Foreign Affairs (A Stone Barrington Novel)

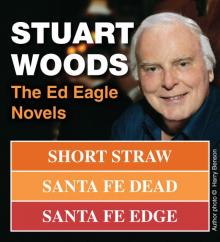

Foreign Affairs (A Stone Barrington Novel) The Ed Eagle Novels

The Ed Eagle Novels Dirty Work

Dirty Work Fast and Loose

Fast and Loose Worst Fears Realized

Worst Fears Realized D.C. Dead

D.C. Dead Deep Lie

Deep Lie Santa Fe Edge

Santa Fe Edge Bel-Air dead sb-20

Bel-Air dead sb-20 The Short Forever

The Short Forever Run Before the Wind

Run Before the Wind Dark Harbor

Dark Harbor Shoot First (A Stone Barrington Novel)

Shoot First (A Stone Barrington Novel) Sex, Lies & Serious Money

Sex, Lies & Serious Money Santa Fe Dead 03

Santa Fe Dead 03 D.C. Dead sb-22

D.C. Dead sb-22 Swimming to Catalina

Swimming to Catalina Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage Hot Mahogany

Hot Mahogany Barely Legal

Barely Legal Imperfect Strangers

Imperfect Strangers Paris Match

Paris Match Mounting Fears

Mounting Fears Mounting Fears wl-7

Mounting Fears wl-7 Shoot Him If He Runs

Shoot Him If He Runs Short Straw

Short Straw Santa Fe Dead

Santa Fe Dead Dead in the Water

Dead in the Water Hothouse Orchid

Hothouse Orchid Below the Belt

Below the Belt Orchid Beach hb-1

Orchid Beach hb-1 Son of Stone sb-21

Son of Stone sb-21 Cold Paradise 07

Cold Paradise 07 Blood Orchid

Blood Orchid Fresh Disasters

Fresh Disasters Lucid Intervals

Lucid Intervals Dishonorable Intentions

Dishonorable Intentions Cut and Thrust

Cut and Thrust The Money Shot

The Money Shot Santa Fe Rules

Santa Fe Rules Iron Orchid

Iron Orchid New York Dead

New York Dead The Short Forever sb-8

The Short Forever sb-8 Son of Stone

Son of Stone Insatiable Appetites

Insatiable Appetites Chiefs

Chiefs Unintended Consequences

Unintended Consequences Reckless Abandon

Reckless Abandon Three Stone Barrington Adventures

Three Stone Barrington Adventures Stuart Woods 6 Stone Barrington Novels

Stuart Woods 6 Stone Barrington Novels Shoot First

Shoot First Indecent Exposure

Indecent Exposure The Run

The Run Bel-Air Dead

Bel-Air Dead Strategic Moves

Strategic Moves Cold Paradise

Cold Paradise