- Home

- Stuart Woods

Lucid Intervals Page 13

Lucid Intervals Read online

Page 13

“I wanted to tell you, before the others arrive, that Jim Hackett met with our intellectual property people this afternoon, and they pleased him. He’s on board with Strategic Services, and he’s said that if we do a good job, he’ll give us more business.”

“I’m delighted to hear it,” Stone said.

“You’ll find your rainmaking reflected in your bonus.”

“I’m delighted to hear that, too.”

“Jim has also said that he’d like you to take on some projects for him.”

“I’m glad to do that as long as you’re on board with it.”

“I am.”

“Did he say what sorts of things he’d like me to do?”

“No. In fact he specified that, while nothing he assigns you will be a conflict of interest with Woodman and Weld, the details of your assignments would remain strictly between you and him. I’ll rely on you to avoid conflicts.”

“I will do so.”

Felicity came downstairs and was reintroduced to the Eggerses, then the doorbell rang, and the former commissioner and his wife, Mitzi, walked in. It was the first time Stone had seen them since the wedding. Stone shook the commissioner’s hand, and Mitzi offered him a cheek while Felicity observed, then was introduced.

Jim Hackett was the last to arrive, with a beautiful woman called Vanessa, to whom, Stone surmised, Hackett was not married. They settled in for cocktails, while the waiter brought hot hors d’oeuvres.

“Stone,” Hackett said, “I expect Bill has told you I met with his people this afternoon.”

“Yes, he has.”

“I was pleased with what I heard, and I thank you for arranging it,” Hackett said. “Dame Felicity, it’s good to see you again after so much time has passed.”

“I’m pleased to see you, Mr. Hackett,” Felicity replied.

“It’s just plain Jim, please.”

“And it’s just plain Felicity.” Her gaze seemed to be boring into Hackett. “We met at a dinner party in London some years ago, as I recall.”

“That’s correct.”

“I thought at the time you seemed familiar. Had we ever met before that?”

“No, I don’t believe so, though I did meet your father once, at lunch at the Garrick Club. He was a very impressive gentleman.”

“The Garrick was his favorite,” Felicity said. “I understand you are a native of the Shetland Islands.”

“I am.”

“You grew up there?”

“Yes. My father was a crofter-he tended the sheep-and my mother was the weaver.”

“You’ve made quite a leap from those days, haven’t you?”

“From those days to these required a number of leaps,” Hackett said. “The army got me out, and then I got out of the army.”

“How did you come to be in the security business?”

“I was in the Paratroop Regiment, and on occasion we served as armed guards for various high-ranking officers and other dignitaries. A mate of mine left the regiment and joined a security firm, and then invited me to join when my enlistment was up. The two of us were adept at devising new security procedures, and eventually we went out on our own. My partner was killed in a car-bomb explosion, and I was left with the business.”

“What was his name?” she asked.

“Tim Timmons,” Hackett replied. “He had no family, so his half of the business came to me.”

Stone could practically see her memorizing this information.

STONE HAD PICKED particularly good wines from his cellar, and they went down well at dinner. Even Felicity and Mitzi seemed to take to each other, and Hackett went out of his way to be charming to Felicity. Stone tried to just watch and listen. The waiter appeared to be doing his job with Hackett’s wineglasses.

WHEN THE GUESTS had gone, Stone went into the kitchen and found Bob Cantor. “How did it go?” he asked.

“I’ve got clear prints of the thumb and four fingers of his right hand,” Bob said, handing Stone a sheet of paper. “I’ve scanned and printed them for you.”

“Great job,” Stone said. “Talk to you later.” Stone went back into the living room and handed Felicity the prints. “All five fingers, right hand,” he said.

“Perfect,” she replied. “I’ll get them checked in the morning.”

They went upstairs and undressed for bed. “Well,” he asked, “what did you think about Hackett?”

“I was mesmerized,” she said.

“Was there anything about him that reminded you of Stanley Whitestone?”

“Everything and nothing. First I would think that I had detected some word or movement that was Whitestone, then it would be gone, submerged in Hackett’s personality. He gave a bravura performance.”

“So you think it was a performance?”

“At least to the extent that everyone performs at a good dinner party, and, by the way, it was a good dinner party. You’re an excellent host.”

“I suppose your people will be checking out this Tim Timmons?”

“Oh, certainly,” she said, “and I expect we’ll find that the facts will jibe with Hackett’s account of them.”

“Then why bother?”

“Because everyone makes mistakes, even James Hackett, and when he does, I want to be on top of things.”

“I have to tell you that I’m convinced Hackett is who he says he is.”

“Why?”

“Because nobody could so completely morph his identity into that of another. I mean, you knew Whitestone, and Hackett had no hesitation in talking to you all evening.”

“You know the films of Laurence Olivier, don’t you?”

“Yes, of course.”

“That’s what Olivier did-submerge himself into character-and I think that’s what Hackett has done. I think Hackett is the Olivier of liars.”

“What is Whitestone’s background?”

“You’ve heard some of it: Eton and Cambridge, recruited there.”

“Who was his father?”

“The bastard son of a marquess who was sent into the church and served out his years as a small-parish vicar.”

“Has all that been substantiated?”

“Of course. When one is at both Eton and Cambridge, one leaves indelible footprints that anyone can follow.”

“Hackett says that when Whitestone met him, seeking employment, he said he was Harrow and Sandhurst, son of an army colonel.”

“A person with such a background would leave equally indelible footprints and if he lied would easily be found out. It is impossible to believe that Whitestone would have invented such an easily penetrated legend.”

“What about Hackett’s ‘legend,’ as you put it?”

“More difficult, at least his early years. The Paratroop Regiment is another thing, though. After all, they keep records.”

“And you’ve already read them?”

“It’s being looked into,” Felicity said.

Stone reflected that he would not enjoy Felicity looking into some lie of his own.

34

Stone was at his desk the following morning when Joan buzzed him. “Mr. Jim Hackett on one,” she said.

Stone picked up the phone. “Good morning, Jim,” he said.

“A perfectly wonderful dinner last night, Stone, and with very fine company.”

“I’m glad you enjoyed it, Jim. We were happy to have you.”

“Dame Felicity turned out to be much more… approachable than I had surmised from our first meeting.”

“A couple of glasses of Champagne will do that.”

“Well, thanks again. Now to business: you’re mine for the next two, two and a half weeks. I’ve cleared this with Bill Eggers, so clear your decks.”

“All right. What do I do?”

“Someone is sitting in your outer office at this moment who will explain everything. I probably won’t speak to you again until you’ve completed your assignment, so have a good time.”

“I’ll try,” Stone

said, but Hackett had already hung up.

Joan buzzed. “A Ms. Ida Ann Dunn to see you, representing Mr. James Hackett.”

“Send her in,” Stone said.

A handsome woman of about fifty entered his office carrying a satchel and followed by Joan, who was carrying two other cases. “Good morning, Mr. Barrington,” she said, dropping her heavy satchel on his desk and opening it.

“Please call me Stone.”

“And you may call me Ida Ann,” she replied, hefting a large three-ring notebook from her satchel and dropping it with a thump before him. “Over the next five days or so, you will memorize this,” she said. The cover read Operators Manual, Cessna 510. “And this,” she said, placing a smaller book on top of it, the title of which was Garmin G-1000 Cockpit Reference Guide.

“After the five-day study period with me, you will meet Mr. Dan Phelan, who will instruct you in the actual flying of the Cessna 510. After thirty or forty hours in the airplane, you’ll take a check ride with an FAA examiner, who will issue you a type rating for the 510. Any questions? No, never mind. I’ll ask the questions; you start reading.”

Stone opened the operator’s manual. “Why am I doing this?” he asked.

“If you’ll forgive me, Mr. Barrington-Stone-that’s a rather stupid question. You are doing this because Mr. Hackett is paying you to do so.”

“Of course,” Stone replied. He picked up the phone and buzzed Joan.

“Yes?”

“Clear my schedule for the next two weeks,” he said. “Make that two and a half weeks.”

“That will be easy,” Joan replied. “The only thing we have scheduled for the next two and a half weeks is a visit from the Xerox man and, probably, several visits from Herbie Fisher.”

“You deal with the first fellow, then tell Mr. Fisher I’ll be unavailable. And hold all my calls, except those of Felicity Devonshire.”

“You betcha,” she replied and hung up.

Ida Ann Dunn now had a laptop projector set up on the conference table and a screen hung on a wall. “Come over here, please, Stone, and bring the operator’s manual with you.”

Stone took a seat at the conference table, and Ida Ann began. By the time Stone was allowed to have a sandwich at the conference table, she had covered structural systems, electrical systems and lighting with slides and animation, while he kept up the pace in the manual. She ate wordlessly, flipping through her notes.

After lunch, Ida Ann covered the master warning system, the fuel system, auxiliary power system and power plant. Promptly at five p.m., Ida Ann switched off the projector and handed Stone several sheets of paper.

“Quiz time,” she said. “As you will note, the examination is multiple choice. You have forty minutes.”

“May I be excused to go to the restroom?” Stone asked.

“Be quick about it,” she replied.

Stone was quick, and then he tackled the exam.

Ida Ann ran quickly through it. “You missed a question,” she said. “Let’s review the fuel system again.”

Twenty minutes later, satisfied that he understood his error, she dismissed him, said she would see him at nine the following morning, then was gone.

Stone stood up and stretched, rubbing his neck.

“And what was that all about?” Joan asked from the doorway.

“I’m being taught to fly a jet airplane,” he said.

“At the conference table?”

“First, ground school, then flying.”

“And Hackett is paying you to do this?”

“He is. Call Eggers’s office later this week and find out how much to bill him.”

“Will do. Oh, Felicity called and said she’d meet you at Elaine’s at eight-thirty.”

“Then I have time for a nap,” Stone said, heading upstairs, exhausted.

STONE ARRIVED AT Elaine’s to find Dino already there, as usual, and the two ordered drinks while they waited for Felicity.

“How was your day?” Dino asked amiably.

“You won’t believe it,” Stone replied. “I spent it in ground school, learning to fly a Cessna Mustang.”

“Isn’t that a jet?”

“It is.”

“But you don’t own a jet.”

“I do not.”

“Are you planning to buy one?”

“I have a new client, Jim Hackett, who says that if I come to work for him, I’ll be able to buy one next year.”

“You’re leaving Woodman and Weld?”

“No. Hackett is hiring me through the firm for special projects.”

“And the first special project is learning to fly a jet?”

“You guessed it.”

“And he’s paying you for this?”

“You guessed it again.”

“How long will it take?”

“Two, two and a half weeks.”

“You can learn to fly a jet that fast?”

“You forget, I already know how to fly; I’m just learning a new airplane.”

Felicity made her entrance forty minutes late. “Apologies,” she said. “Drink.”

Stone waved at a waiter and secured a Rob Roy.

“How was your day?” she asked.

Stone gave her a brief account of it.

“And it takes only two weeks to learn?”

“If I’m lucky.”

“I’m not flying with you,” she said. “Let me know when you have a hundred hours.”

“I already have three thousand hours,” he said.

“A hundred hours in type.”

“Right. What have your day’s investigations produced?”

And she began to complain.

35

Felicity took a sip of her Rob Roy. “Turns out that the records of the Parachute Regiment at the time Hackett alleges he was a member are stored in an army warehouse in Aldershot, south of London.”

“So?” Stone asked. “Are they available?”

“They are available,” she replied, “but they are a sodden, mold-infested mess, having been placed in a corner of the warehouse that has been flooded twice by huge rainstorms in the past two years.”

“What can you do about that?”

“I’ve been able to spare two document specialists who are trying to dry and extract the relevant pages,” she replied, “but quite frankly, if I had a dozen people to spare for a year, that might not be enough manpower or time to find Hackett’s and Timmons’s records.”

“In this country,” Stone said, “if you are fingerprinted for anything-military service, for instance-your prints end up in the FBI database. Is the same true in Britain?”

“Yes, and we’ve already been to the police, but that far back, none of the records have been computerized, so a search of paper records has to be done by hand. The problem that arises is that hardly anyone with the police is old enough to know how to accomplish such a search, as opposed to a computer search. We are being defeated by the lack of old skills among younger employees. What’s more, the records from that time have also been stored in a warehouse in boxes that were poorly labeled.”

“So you have no hope of finding a record of Hackett’s fingerprints?”

“Very little hope. It’s just barely possible that we might get lucky.”

“I have a suggestion,” Stone said.

“Please make it a good one.”

“Hackett is a naturalized American citizen,” Stone pointed out. “He would have been fingerprinted at the time of submitting his application for citizenship, and the State Department would have his application on file.”

Felicity brightened. “That is a very good suggestion, Stone. I’ll have the ambassador make inquiries tomorrow.” She wrinkled her brow. “I wonder what the State Department would make of a foreign ambassador inquiring about the fingerprints of an American citizen.”

“Good point,” Stone said. “It might be better to have your police make the request through the FBI.”

“Perhaps so,” she

said. “I’ll phone the commander of the Metropolitan Police tomorrow and make the request.” She took another sip of her drink. “Why do you suppose Hackett wants you to learn to fly a jet aeroplane?”

“I can only guess,” Stone said. “When he was trying to persuade me to come to work for him he told me that, in a year, I’d be able to afford my own jet.”

“That must be very alluring for you,” Felicity said.

“It’s interesting, but not alluring.”

“I’ll bet you’ve had little-boy fantasies for years about flying your own jet.”

“I’m afraid you’re right,” Stone admitted.

“Then why don’t you go to work for him?”

“That’s what I’m doing right now; Woodman and Weld has assigned me to Hackett.”

“So what’s the difference?”

“The difference is, if you can prove that Hackett is Whitestone, you’re going to do something terrible to him, and Strategic Services would probably come crashing down without him to run it. Then where would I be?”

“Not at Woodman and Weld.”

“Exactly.”

“If that happened,” Dino pointed out, “you could sell your hypothetical jet and live on the proceeds.”

“Sell my hypothetical jet?” Stone asked. “Never!”

Felicity managed a laugh.

“You should do that more often,” Stone said. “You’ve been working too hard.”

“No harder than usual.”

“Who’s minding the store in London while you’re here?”

“I have a very competent deputy who handles the administrative side. The rest I am doing from the office here.”

“Don’t you ever have to make an appearance?” Dino asked.

“Eventually,” Felicity replied. “It’s not as though I’m the prime minister or some other public figure. I don’t have to appear in the newspapers or on television every day or be interviewed by anyone.”

“How much longer can I count on having you as my houseguest?” Stone asked.

“At least until we get to the bottom of the Hackett/Whitestone riddle,” she replied.

“Then I’ll have to work more slowly,” Stone said.

36

Beverly Hills Dead

Beverly Hills Dead Shakeup

Shakeup Hush-Hush

Hush-Hush Wild Card

Wild Card A Delicate Touch

A Delicate Touch Dead Eyes

Dead Eyes Stealth

Stealth Loitering With Intent

Loitering With Intent Grass Roots

Grass Roots Scandalous Behavior

Scandalous Behavior L.A. Times

L.A. Times L.A. Dead

L.A. Dead Class Act

Class Act Dirty Work sb-9

Dirty Work sb-9 Bombshell

Bombshell Standup Guy

Standup Guy Quick & Dirty

Quick & Dirty Stuart Woods Holly Barker Collection

Stuart Woods Holly Barker Collection Standup Guy (Stone Barrington)

Standup Guy (Stone Barrington) Capital Crimes

Capital Crimes Kisser

Kisser Hot Pursuit

Hot Pursuit Choke

Choke Blue Water, Green Skipper: A Memoir of Sailing Alone Across the Atlantic

Blue Water, Green Skipper: A Memoir of Sailing Alone Across the Atlantic Under the Lake

Under the Lake Unnatural acts sb-23

Unnatural acts sb-23 Doing Hard Time

Doing Hard Time White Cargo

White Cargo The Prince of Beverly Hills

The Prince of Beverly Hills Severe Clear

Severe Clear Bel_Air Dead

Bel_Air Dead Severe Clear sb-24

Severe Clear sb-24 Unnatural Acts

Unnatural Acts Dirt

Dirt Foreign Affairs

Foreign Affairs Unbound

Unbound Family Jewels

Family Jewels Foreign Affairs (A Stone Barrington Novel)

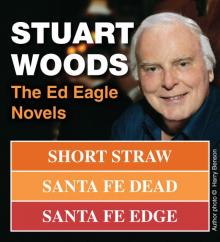

Foreign Affairs (A Stone Barrington Novel) The Ed Eagle Novels

The Ed Eagle Novels Dirty Work

Dirty Work Fast and Loose

Fast and Loose Worst Fears Realized

Worst Fears Realized D.C. Dead

D.C. Dead Deep Lie

Deep Lie Santa Fe Edge

Santa Fe Edge Bel-Air dead sb-20

Bel-Air dead sb-20 The Short Forever

The Short Forever Run Before the Wind

Run Before the Wind Dark Harbor

Dark Harbor Shoot First (A Stone Barrington Novel)

Shoot First (A Stone Barrington Novel) Sex, Lies & Serious Money

Sex, Lies & Serious Money Santa Fe Dead 03

Santa Fe Dead 03 D.C. Dead sb-22

D.C. Dead sb-22 Swimming to Catalina

Swimming to Catalina Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage Hot Mahogany

Hot Mahogany Barely Legal

Barely Legal Imperfect Strangers

Imperfect Strangers Paris Match

Paris Match Mounting Fears

Mounting Fears Mounting Fears wl-7

Mounting Fears wl-7 Shoot Him If He Runs

Shoot Him If He Runs Short Straw

Short Straw Santa Fe Dead

Santa Fe Dead Dead in the Water

Dead in the Water Hothouse Orchid

Hothouse Orchid Below the Belt

Below the Belt Orchid Beach hb-1

Orchid Beach hb-1 Son of Stone sb-21

Son of Stone sb-21 Cold Paradise 07

Cold Paradise 07 Blood Orchid

Blood Orchid Fresh Disasters

Fresh Disasters Lucid Intervals

Lucid Intervals Dishonorable Intentions

Dishonorable Intentions Cut and Thrust

Cut and Thrust The Money Shot

The Money Shot Santa Fe Rules

Santa Fe Rules Iron Orchid

Iron Orchid New York Dead

New York Dead The Short Forever sb-8

The Short Forever sb-8 Son of Stone

Son of Stone Insatiable Appetites

Insatiable Appetites Chiefs

Chiefs Unintended Consequences

Unintended Consequences Reckless Abandon

Reckless Abandon Three Stone Barrington Adventures

Three Stone Barrington Adventures Stuart Woods 6 Stone Barrington Novels

Stuart Woods 6 Stone Barrington Novels Shoot First

Shoot First Indecent Exposure

Indecent Exposure The Run

The Run Bel-Air Dead

Bel-Air Dead Strategic Moves

Strategic Moves Cold Paradise

Cold Paradise