- Home

- Stuart Woods

L.A. Times Page 13

L.A. Times Read online

Page 13

“Were these rights very valuable to you, Mr. Vincent?”

“Not in a major way. The book was published in the nineteen-twenties and is little known today. A friend gave it to me to read last year sometime, and it occurred to me that it might make a film. I finally got around to looking into the rights. I didn’t even know who controlled them until last week. If you don’t mind my saying so, it seems that interviewing me is quite a long way from a hit-and-run incident.”

“It was more than that,” the policeman said. “Mr. Moriarty wasn’t actually killed by the car. The driver got out and knifed him, just to be sure.”

“Good God!” Michael said. “That’s pretty brutal.”

“Yes, it is.”

“So I suppose you’re interviewing anybody who had anything to do with him.”

“That’s right, and there are surprisingly few people who had anything to do with him.”

“It’s really ironic that he should be murdered,” Michael said. “Wallace Merton told me that Moriarty was a dying man—a bad liver.”

“That’s what we learned from his part-time secretary. Mr. Vincent, can you tell me where you were between eight and nine o’clock this morning?”

Michael didn’t miss a beat. “Of course. I got up later than usual this morning. I didn’t leave the house until around nine-thirty, and I was in the office before ten.”

“Is there anyone who can corroborate that?”

“Yes, my secretary can tell you what time I arrived here this morning, and the woman I live with can tell you when I left the house.”

“And her name?” His notebook was poised.

“Vanessa Parks.” He gave them the phone number.

“What kind of car do you drive, Mr. Vincent?”

“A Porsche Cabriolet.”

“Color?”

“Black.”

“Do you know anyone who drives a red Cadillac?”

“No. Everybody in this business seems to drive a foreign car—just take a look in the lot outside.”

The policeman smiled. “I noticed.” He looked around the room. “This looks like a room I saw in a movie once.”

“This was the study in a nineteen-thirties movie called The Great Randolph.”

“That’s it! I knew I’d seen it somewhere.”

“You’re a movie fan, then?”

“Absolutely.”

“Would you like a little tour of the lot?”

“I’d love it some other time, Mr. Vincent, but we’ve got a lot on our hands this afternoon.”

“Call my secretary anytime, and she’ll arrange it for you.”

“And when can I expect to see Pacific Afternoons on the screen?”

“Oh, that’s hard to say. I only bought the rights today, and a screenplay has to be written. I’d say a year, at the earliest.”

“So you did get the rights after all?”

“Mr. Merton and I reached agreement very quickly. I don’t think he’d ever had another offer. By the way, would you like his number?”

“Thanks, we already have it.”

Michael stood up. “Gentlemen, if there’s nothing further…”

The policemen rose, then stopped at the office door. “There were two men in the Cadillac,” Rivera said.

“Oh? Any leads?”

“One or two. It was a professional job; we know that much.”

“Sounds interesting. Tell you what, Sergeant, when you’ve made an arrest give me a call, and let’s talk about it. Might be a movie in it.”

“Maybe I’ll do that, Mr. Vincent,” Rivera said.

“Don’t wait until you’re ready to go to trial, though. Call me the minute you’ve made an arrest, before there’s a lot of publicity.” He smiled. “I wouldn’t want to get into a bidding war.”

The cop laughed and shook his hand. “A bidding war sounds good to me.” He gave Michael his card. “Call me if you think of anything else I should know.”

Michael gave him his card. “Same here. True crime stuff is always good for the movies.” He waved and went back into his office.

He waited until he was sure they’d left the building, then called Vanessa.

“Hello?”

At least she was awake. “Hi, babe. You remember our conversation of this morning?”

“Yes,” she said exasperatedly, “we made love and took a shower together, and you didn’t leave until nine-thirty.”

“You’ll be getting a call from a policeman who’ll ask you about that.”

“What’s this about, Michael?”

Stick close to the truth. “Last week I tried to buy the screen rights to Pacific Afternoons from a lawyer named Moriarty. He wouldn’t sell them to me, so I went to the lawyer who represents the college that owns the rights, and he sold them to me. Then Moriarty gets run down by a car—murdered apparently—and the cops came to see me, since I was in Moriarty’s diary.”

“So where were you this morning?”

Michael stopped breathing. “Didn’t you wake up at all when I got up?”

“No.”

He relaxed. “Well, I was right there, babe. I fixed myself some breakfast as usual, and I decided to read a script before leaving for the studio. That’s why I was late.”

“So why didn’t you just tell the police that?”

“Because you couldn’t back me up if you were asleep.”

“Oh.”

“See you later, babe. We’ll drive out to Malibu for dinner, okay?”

She brightened. “Okay.”

“I gave the cops the number; they’ll call.”

“Okay, I know what to say.”

He hung up. “Margot,” he called out, “get me Leo.”

Leo took the call. “Yeah, kid?”

“Just wanted to let you know I’ve sewed up the rights to Pacific Afternoons.”

“How much?”

“Twenty grand against forty.”

“You’re my kind of guy. See you.” Leo hung up.

Michael hung up, too. He was thinking of growing his beard again.

On the way home, Michael stopped his car at a phone booth and called a number Tommy Pro had given him.

A recorded voice answered. “Please enter the number of a touch-tone phone where you can be reached at this hour.” There was a series of beeps.

Michael tapped in the number of the phone booth, then hung up and waited nervously. Ten minutes passed, then the phone rang. He snatched up the receiver. “Tommy?”

“Where are you calling from?”

“A phone booth on Pico.”

“How are you, kid? What’s up?”

“Tommy, you very nearly got me hung up on a murder rap. What the hell were you thinking of?”

Tommy was immediately apologetic. “Listen, I’m sorry about that, kid. The guy was recommended to me highly; who knew he was going to be a cowboy? Don’t worry, he’s already out of the picture.”

“Tommy, people saw me in that car with him. The cops have already been to my office.”

“That’s natural; after all, you had a meeting with the guy, right? Just be cool and everything will be okay.”

“Tommy, I don’t know how you could put me in this position.”

Tommy’s voice hardened. “Your problem is solved, right?”

“Yes, but…”

“I gotta go.” Tommy hung up.

Michael was left with the dead phone in his hand.

CHAPTER

26

Michael sat at a table at a McDonald’s on Santa Monica Boulevard and watched the door for Barry Wimmer. He recognized the short, bearded man from his own description and waved him toward the table. Wimmer stopped at the counter and picked up a Big Mac and fries first.

Michael shook the man’s hand as he sat down.

“First meeting I ever took at McDonald’s,” Wimmer said.

“Morton’s didn’t seem appropriate.”

Wimmer emitted a short, rueful laugh. “No, I don’t guess you’

d want to be seen with me at Morton’s.”

“Or any other industry hangout,” Michael said.

Wimmer looked ill for a moment. “Thanks for reminding me,” he said bitterly.

“When did you get out?” Michael asked.

“Four months ago.”

“How are you making a living?”

“I’ve worked up a couple of budgets for friends,” Wimmer replied, attacking the Big Mac.

Michael reached into the briefcase beside him and fished out a budget for Pacific Afternoons. “Tell me what you think of this,” he said, handing Wimmer the document across the table.

Wimmer put down his burger and began leafing through the pages, chewing absently. He took his time. “This is as tight as anything I’ve ever seen,” he said finally, “but it’ll work if you can shoot outside L.A.”

“I want to shoot in Carmel.”

Wimmer nodded. “If you’ve already got a budget, why did you want to see me?”

“I’ve heard some good things about you.”

“Not recently, I guess. My name’s mud in this town.”

“Very recently. I heard that you may have taken various studios for as much as five million dollars over the past ten years.”

“I got sent away for two hundred grand,” Wimmer said. “That’s all I’ll cop to.”

“What did you do with all the money?” Michael asked. “I’m curious.”

“I lived well,” Wimmer said.

“You lived high, too, from what I’ve heard.”

Wimmer smiled ruefully. “You could say that.”

“Are you still using?”

“Prison didn’t do much for me, but it got me off cocaine. There was a pretty good therapy program.”

“Out of all the money you took did you save anything?”

Wimmer snorted. “If I had, do you think I’d have gone to jail for two hundred grand? I’d have made restitution.”

“What are your plans for the future?”

“I was thinking of starting a private course for production management.”

“That should buy groceries.”

“And not much else.”

“Are you interested in getting back into the business?”

“Doing what? Props?”

“As a production manager.”

Wimmer stopped chewing and looked at Michael for a long time. “Don’t fuck around with my head, mister.”

“I’m quite serious.”

“On this project?” He tapped the budget.

“On this project.”

“You think you could trust me not to steal?”

Michael wiped his mouth and threw his napkin onto the table. “Barry, if you come to work for me, stealing will be your principal duty.”

Wimmer stared at Michael, apparently stunned into silence.

“Let me ask you something,” Michael said. “How did you get caught on the two hundred thousand?”

Wimmer swallowed hard and fiddled with his french fries. “I had a producer who was as smart as I was.”

“I’m smarter than you are, Barry,” Michael said. “And if you were stealing from my production, I would catch you at it.”

Wimmer nodded. “I see,” he said. “You won’t catch me, is that it?”

“That’s it,” Michael said.

“We split what I can take?”

“Not quite. Not fifty-fifty.”

“What did you have in mind?”

“I’ll give you twenty percent of anything you can rake off the budget.”

“What happens if we get caught?”

“Who’s going to catch you, if not me?”

“Doesn’t Centurion have any controls at all?”

“Of course they do, and very good controls, too. But from what I’ve heard, you’re something of a genius at fooling the studios.”

“You could say that,” Wimmer agreed.

“What’s the number at the bottom of that budget?” Michael asked, nodding toward the document.

“Eight million, give or take.”

“What sort of budget would that be in this town?”

“Tight, under any circumstances; but who’s your star?”

“Robert Hart.”

Wimmer’s eyes widened. “And your writer?”

“Mark Adair.”

“Director?”

“A very bright kid from UCLA Film School.”

“Then eight million is an impossible budget, even with a kid director.”

“Would ten million be more in line?”

“Fifteen million would be more in line, if everything were cut to the bone and Hart took points instead of salary.”

“Suppose we settle at nine and a half million. We shoot the picture for eight million, and you, employing your special genius, flesh it out to nine million five. You think you could do that?”

“For twenty percent? In the blink of an eye.”

Michael smiled. “That’s what I thought.”

“What do I get paid for the picture?”

“You’ll work cheap. Nobody will be surprised; at this point you’d take just about any job, wouldn’t you?”

“I would.”

“You’ve never, ah, collaborated with anybody on something like this, have you?”

“No.”

“Well, we had better get a couple of things straight. First of all, there will never be any transaction of cash between you and me. Every week, you’ll go to the local Federal Express office and send eighty percent of the rake-off to an address I’ll give you. I want you to remember at all times that I’m smarter than you, Barry; that’s very important to our working relationship.”

“Okay, you’re smarter than me. I can live with that.”

“My share of the money is going to be untraceable; I’ll help you see that your share is, too. It is not in my interests for you to get caught.”

“What happens if I do get caught? I mean, if you’re underestimating Centurion’s controls?’

“I assure you that I’m not, but I’ll give you a straight answer to your question: If you get caught, you’ll take the fall. I’ll testify against you myself; there won’t be any way you can implicate me, and if you try, I’ll make things even worse for you.”

“You’re a sweet guy,” Wimmer said.

“Is anybody else in town going to hire you?”

“Nope.”

“Then you’re right; I’m a sweet guy—as long as things go smoothly. You fuck up, and you’re back in jail; you fuck me, and—I want you to take this seriously, Barry—I’ll see you dead. That’s not a euphemism; it’s a serious promise.”

Wimmer stared at Michael.

“On the brighter side, you’ll make some very nice money, and you’ll be seen to rehabilitate yourself. I’m going to make a lot of pictures, and as long as our relationship works out, you’ll have a job.”

“That sounds good,” Wimmer said.

“So we understand each other? I wouldn’t want there to be any misunderstanding.”

“We understand each other completely,” Wimmer said firmly.

“Good.” Michael extended his hand and Wimmer shook it. “Be at my office on the Centurion lot first thing tomorrow morning. I’ll have a desk ready for you, and I’ll leave a pass at the gate.”

“Yes, sir,” Wimmer said, smiling.

CHAPTER

27

Monday night at Morton’s. The crème de la crème of the motion picture industry sat in the dimly lit restaurant on Melrose Avenue and displayed their standing to each other. Michael and Vanessa sat with Leo and Amanda Goldman at a table between that of Michael Ovitz, head of the talent agency Creative Artists Agency, and that of Peter Guber, head of Sony Pictures. Michael had been introduced to and had exchanged desultory chat with both men. Being in their presence, on equal terms, gave him a satisfaction he had not felt since he had made his deal with Centurion.

After dinner, when the women had adjourned to the ladies’ room, Leo put h

is elbows on the table and leaned forward. “There’s a guy I’d like you to consider to direct Pacific Afternoons,” Leo said. “His name is Marty White.”

“I appreciate the suggestion, Leo,” Michael said, “but I think I’ve already found a director.”

Leo’s eyebrows went up. “Who? How could you do that without my knowing about it?”

“Leo, I shouldn’t have to remind you that I don’t need your approval to hire a director.”

“Jesus fucking Christ, I know that; what I don’t know is why I didn’t know about it. I know everything that goes on at my studio.”

“So I’ve heard,” Michael said.

“You couldn’t take a meeting with somebody about that job that I wouldn’t know about. Not with any director in town.”

“This guy has never directed anything. That’s why you don’t know about him.”

Leo leaned forward and made an effort to lower his voice. “You’ve hired some schmuck who never directed a picture?”

“Well, he’s directed things at school.”

“At school!”

“He’s at UCLA Film School.”

“You hired a student to direct this movie?”

“Leo, I was a student at film school when I produced Downtown Nights.”

“That’s different.”

“No, it’s not different; it’s exactly the same.”

“I think you’ve gone crazy, Michael.”

“Did you screen the reel?”

“What reel?”

“Leo, I sent you the kid’s reel last Wednesday.”

“I didn’t get to it yet.”

“Well, if you had gotten to it, your blood pressure would be a lot lower right now.”

“So, what’s on the reel?”

“A scene from a Henry James novel that was so good I couldn’t believe it.”

“Just one scene?”

“A scene of eight pages with a long tracking shot, an orchestra, and seven speaking parts.”

“Who’s this kid?”

“His name is Eliot Rosen.”

“Well, at least he’s Jewish.”

Michael laughed.

“Are you Jewish, Michael? I could never figure it out.”

“Half,” Michael lied. “My mother.”

“What was your father?”

Beverly Hills Dead

Beverly Hills Dead Shakeup

Shakeup Hush-Hush

Hush-Hush Wild Card

Wild Card A Delicate Touch

A Delicate Touch Dead Eyes

Dead Eyes Stealth

Stealth Loitering With Intent

Loitering With Intent Grass Roots

Grass Roots Scandalous Behavior

Scandalous Behavior L.A. Times

L.A. Times L.A. Dead

L.A. Dead Class Act

Class Act Dirty Work sb-9

Dirty Work sb-9 Bombshell

Bombshell Standup Guy

Standup Guy Quick & Dirty

Quick & Dirty Stuart Woods Holly Barker Collection

Stuart Woods Holly Barker Collection Standup Guy (Stone Barrington)

Standup Guy (Stone Barrington) Capital Crimes

Capital Crimes Kisser

Kisser Hot Pursuit

Hot Pursuit Choke

Choke Blue Water, Green Skipper: A Memoir of Sailing Alone Across the Atlantic

Blue Water, Green Skipper: A Memoir of Sailing Alone Across the Atlantic Under the Lake

Under the Lake Unnatural acts sb-23

Unnatural acts sb-23 Doing Hard Time

Doing Hard Time White Cargo

White Cargo The Prince of Beverly Hills

The Prince of Beverly Hills Severe Clear

Severe Clear Bel_Air Dead

Bel_Air Dead Severe Clear sb-24

Severe Clear sb-24 Unnatural Acts

Unnatural Acts Dirt

Dirt Foreign Affairs

Foreign Affairs Unbound

Unbound Family Jewels

Family Jewels Foreign Affairs (A Stone Barrington Novel)

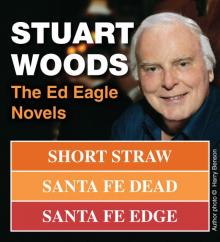

Foreign Affairs (A Stone Barrington Novel) The Ed Eagle Novels

The Ed Eagle Novels Dirty Work

Dirty Work Fast and Loose

Fast and Loose Worst Fears Realized

Worst Fears Realized D.C. Dead

D.C. Dead Deep Lie

Deep Lie Santa Fe Edge

Santa Fe Edge Bel-Air dead sb-20

Bel-Air dead sb-20 The Short Forever

The Short Forever Run Before the Wind

Run Before the Wind Dark Harbor

Dark Harbor Shoot First (A Stone Barrington Novel)

Shoot First (A Stone Barrington Novel) Sex, Lies & Serious Money

Sex, Lies & Serious Money Santa Fe Dead 03

Santa Fe Dead 03 D.C. Dead sb-22

D.C. Dead sb-22 Swimming to Catalina

Swimming to Catalina Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage Hot Mahogany

Hot Mahogany Barely Legal

Barely Legal Imperfect Strangers

Imperfect Strangers Paris Match

Paris Match Mounting Fears

Mounting Fears Mounting Fears wl-7

Mounting Fears wl-7 Shoot Him If He Runs

Shoot Him If He Runs Short Straw

Short Straw Santa Fe Dead

Santa Fe Dead Dead in the Water

Dead in the Water Hothouse Orchid

Hothouse Orchid Below the Belt

Below the Belt Orchid Beach hb-1

Orchid Beach hb-1 Son of Stone sb-21

Son of Stone sb-21 Cold Paradise 07

Cold Paradise 07 Blood Orchid

Blood Orchid Fresh Disasters

Fresh Disasters Lucid Intervals

Lucid Intervals Dishonorable Intentions

Dishonorable Intentions Cut and Thrust

Cut and Thrust The Money Shot

The Money Shot Santa Fe Rules

Santa Fe Rules Iron Orchid

Iron Orchid New York Dead

New York Dead The Short Forever sb-8

The Short Forever sb-8 Son of Stone

Son of Stone Insatiable Appetites

Insatiable Appetites Chiefs

Chiefs Unintended Consequences

Unintended Consequences Reckless Abandon

Reckless Abandon Three Stone Barrington Adventures

Three Stone Barrington Adventures Stuart Woods 6 Stone Barrington Novels

Stuart Woods 6 Stone Barrington Novels Shoot First

Shoot First Indecent Exposure

Indecent Exposure The Run

The Run Bel-Air Dead

Bel-Air Dead Strategic Moves

Strategic Moves Cold Paradise

Cold Paradise