- Home

- Stuart Woods

Son of Stone Page 15

Son of Stone Read online

Page 15

“Welcome to the big city. How do you like it so far?”

“It’s everything I dreamed it would be,” Peter said.

“You dreamed about living here?”

“Everybody who doesn’t live in New York dreams about living here. I’m no exception. I can go to the movies as often as I like.”

“The movies are your thing, are they?”

“I like the theater, too, but I’m crazy about movies. If you’re not, I’ll probably bore you rigid.”

She laughed. “I like movies, and you don’t seem in the least boring.”

“That’s the nicest thing anybody has said to me in the big city,” he said. He glanced at his watch. “I have an appointment with some editing equipment. If you’ll excuse me, I’ll see you on Saturday.”

“I’ll look forward to it,” she replied. She turned back to the piano and began to play again.

Peter left the recital hall and walked back to the film department, feeling a little light-headed. He felt some other things he hadn’t felt before, too.

37

Alan Ripley switched off the light in his office and, in the gathering dusk, walked across the campus at Herald Academy in tidewater Virginia, kicking at little piles of leaves the wind had gathered. Autumn came late here, but now there was a real nip in the air. He wrapped his muffler tighter.

He climbed the stairs to his small apartment in the faculty residence and switched on the lights, then he lit the already laid fire and backed up to the hearth as it caught. When his backside got too hot to handle he poured himself a small scotch, settled in a leather wing chair near the fire, and picked up the le Carré novel he had been reading. He had just opened the book when the phone rang. He closed the book and grabbed the phone. “Hello?”

“Alan?” A vaguely familiar voice.

“Yes, who’s that?”

“A voice from the past. It’s James Heald.”

Ripley was pleasantly surprised. “James? It’s good to hear from you. I haven’t heard that voice since we left Harvard.”

“Good to hear yours, too.”

“Where are you? What are you doing?”

“I’m teaching set design at the Yale School of Drama.”

“Good for you. I’d heard you were working on Broadway at some point.”

“Yes, but it was too fast a track for me, and the gaps between jobs were too long. I’ve been at Yale for nearly two years, now, and it suits me better.”

“Congratulations. It sounds like a good place to be. How did you find me?”

“Well, I stopped in the dean’s office for a minute last week and I caught a bit of your performance.”

“Performance? What do you mean?”

“Your screen acting performance.”

“You baffle me.”

“Didn’t you act in a student film down there?”

“Oh, Christ, yes. I’m sorry, I didn’t make the connection. We don’t really have a film department as such, and I acted as faculty adviser on a student project last year. I got roped into playing a part. That must have been what you saw.”

“That’s exactly what I saw, and just enough to get the gist of the plot. I must say, I was impressed. Perhaps you missed your calling.”

“Well, if the recession ever catches up with music teachers, maybe I’ll try Broadway or Hollywood.”

“Did you know I went to Herald?”

“No, I didn’t. I don’t expect it’s changed much since you were here.”

“Probably not. I have to tell you that I’m surprised the powers that be down there allowed the film to be made.”

“You baffle me, James. Why shouldn’t they allow it?”

“Did anybody from above read the script?”

“No, I guess not. I haven’t even read it myself.”

“You were the faculty adviser, and you didn’t read the script?”

“No, the boy who directed it came over all Woody Allen and insisted that the actors saw only the pages of the scenes they were appearing in. He was very secretive about the project. I wondered why, at first, but he assured me that there was no nudity, no sex, and only minimal, prep-school-boy bad language.”

“Ah, now I begin to get it.”

“Get what?”

“Well, after I saw the scene in our dean’s office, I filched the script from his secretary’s desk and read it.”

Now Ripley was getting worried. “Was there anything alarming in it?”

“Nothing that would alarm the general public, since it’s only a student film, but you should hope the headmaster never sees the film.”

“Why on earth should I be concerned about that?”

“You obviously don’t get it, Alan. The script fairly closely follows some real events at the school. It would have been before your time, of course—five or six years ago. I could see why you wouldn’t have known. I can also see why the student wanted to keep his film under wraps. I take it you haven’t seen the finished product.”

“No, the boy left school early, and he was still editing, I think. He promised to send me a DVD, but he hasn’t as yet done so.”

“Mmmm, yes.”

“James, exactly what real events does the film follow?”

“Well, as I said, it was before your time there, and after mine. I didn’t hear about this until I attended my tenth reunion. There was some talk about it at that time.”

“Go on.”

“Well, the rough outline is something like this: a master diddles a student, student drops out of school, hangs himself while allegedly doing that sex thing that’s supposed to generate an orgasm with partial asphyxiation—but suicide is a possibility.”

“Good God!”

“Hang on to your hat, my friend, there’s more.”

“The investigation is cursory—small-town Virginia police, you know, but back at Herald, the boy’s death brings attention to bear on a chemistry master. A few weeks later, the master is found dead in his study.”

“Dead how?”

“The supposition is suicide, but the autopsy report does not give a cause of death. But the fellow is a chemistry master, after all, and the feeling is that he mixed up some sort of untraceable potion and offed himself.”

“This is awful,” Ripley said, downing the remainder of his scotch.

“Just one more thing: there was a suspicion in the air that one or more of his students, out to avenge their classmate, may have concocted the potion and somehow introduced it into his system. The police questioned everybody, but they could find no evidence pointing to anyone in particular. By that time, the master’s remains had been cremated, and his ashes scattered on the James River, so the whole business eventually petered out.”

“James,” Ripley said, “is there any way you can get your hands on that script, or the DVD?”

“Nope. The boy asked for both to be returned to him, and they were. He didn’t want anyone to see it. Actually, that may not be a bad thing for you. And, if the headmaster gets wind of the flick, you might want to stick with only the facts you knew before this conversation, which I will keep to myself. After all, being dumb is better than being complicit.”

“You have a point,” Ripley said. “Tell me how this film came to be in your dean’s office.”

“The boy, this Peter Barrington, has applied for admission to the school, and the word is, he had a favorable interview. The dean did tell his secretary that the committee all thought his film was brilliant, the sort of thing that might do well at the indie festivals.”

“You said Barrington?”

“Peter Barrington.”

What the hell? Ripley thought. “His name wasn’t Barrington when he was here. It was Calder.”

“Like the sculptor?”

“Like the actor. So, if he’s accepted, he would matriculate in the fall?”

“It seems so.”

“Well, thanks for the heads-up, James.”

“Not at all, Alan.”

“At le

ast I’ll know what I’m up against if I have to face the headmaster monster.”

“If you get up this way, let me know, and I’ll buy you a bad lunch in our cafeteria.”

“Certainly will, James. Take care.” Ripley hung up and stared into the fire. So now Peter Calder is Peter Barrington? Let’s see, it’s January, he thought. If I start looking now, I might just be able to find a new job before the fall.

He poured himself a second scotch, a larger one.

38

Arrington drove from her rental house to her new property and turned down the long, oak-lined drive. Even from that distance she could see Tim Rutledge waiting for her on the front porch, a roll of blueprints under his arm. He stood stone-still, staring at her as she approached.

Arrington began to take deep breaths, trying to keep her blood pressure from rising. She parked her car out front, then gathered her purse and her briefcase and got out. She walked up the front steps purposefully, tucked her purse under one arm, and held out her hand. “Good morning, Tim,” she said.

He looked at her hand contemptuously, then deigned to shake it briefly. “Good morning,” he said. “Is that all you have to say to me?”

“I’m sure I will have a great deal to say to you, once we get to work, and it will be all business. I believe that has been made clear to you.”

“Well, Barrington called and said he was your lawyer. That was news to me.”

“He has been my attorney for just over a year, and I’m very pleased with him. I trust him to convey to others my exact intentions.”

“Does that include your intentions toward me?”

“It does. Now, shall we get to work?” Without waiting for a reply, she inserted her key in the front door and opened it. She walked into the broad hallway that ran the length of the house, stopped and looked around. “Take notes,” she said.

Rutledge produced a yellow legal pad and pen.

“The color of the wood stain on the floor of the library is not the one I selected; it’s not dark enough.”

“I thought it should be the same as that in the hall,” Rutledge replied.

Arrington walked into the library, set her briefcase on the top of a stepladder, opened it, and took out a stain chart. She dropped it on the floor. “See the X?” she asked. “That’s the color I want on this floor. Please see that it’s sanded and restained immediately. I can see that there’s only one coat of varnish applied, and when the stain is right, I want ten coats, as I specified earlier. Same for the hall.”

“All right,” Rutledge said, making a note.

“I do not want the move-in date changed by so much as an hour, because the ten coats have taken so long to dry. With the varnish I selected you can apply two coats a day, one at eight a.m., another at six p.m.”

“All right,” Rutledge said.

“Where is the shotgun cabinet?” she asked, pointing at a gap in the beautiful paneling, near the fireplace.

“The cabinetmaker made a serious error, and I insisted he remake it. It will be installed tomorrow.”

“When my furnishings arrive, you will find two very fine shotguns and two rifles that belonged to my father. Please be sure that they are securely locked in that cabinet. Where are the keys?”

“The cabinetmaker has them. He had to install the locks.”

“Fine. I don’t want those weapons stolen; they’re worth a fortune.”

“I understand.”

He was beginning to sound more cordial, she thought.

“Listen to me, Arrington,” he said.

She turned to face him. “Yes? Is this about the house?”

“It’s about you and me. You can’t treat me as if I’m some servant who works here, not after what we’ve done in bed.”

Arrington drew back her right hand and delivered a swinging slap that connected with his face, staggering him. He stood, wideeyed, staring at her.

“Don’t you ever again speak to me in that manner, or about anything but this house. Is that perfectly clear?”

Rutledge rubbed his face, which had turned red with anger.

“As you wish,” he said.

“And there’s something you should know: Stone Barrington and I were married on Christmas Day.”

Rutledge turned pale and was blinking rapidly. “Congratulations,” he said weakly.

“Good,” she replied. “Now, let’s have a look at the living room floors.” She led him through the remainder of her list of things to do in the house, then she curtly said good-bye, got into her car, and drove back to her rental house.

39

Stone had slept late on Saturday morning when the phone rang. “Hello?” He coughed.

“Poor baby,” Arrington said, “I woke you. I thought you woke at dawn, regardless of the day.”

“So did I,” Stone replied, pressing the button to raise the head and foot of his bed to a sitting position. “How’s it going down there?”

“Better,” she said. “It was a mess when I got here, but I got it sorted out. The floors in the library and living room had been stained improperly, but that is being redone, and there were a dozen other things that needed attention. Moving-in day is next Friday.”

“Do you want me to come down there and help?”

“You’d just be in the way. You don’t know where anything goes, and I have a carefully worked out plan for where every piece of furniture and box should land. Anyway, I don’t want you to see it until it’s perfect.”

“I can handle perfect,” Stone said.

“What are you doing with yourself today?”

“Chaperoning Peter and a girlfriend.”

“Girlfriend? What’s this?”

“She’s a music student at Knickerbocker, and he says she’s going to score his movie. He’s pretty excited about it. They’re going to lunch at the Brasserie, then coming here to watch the film.”

“And you’re going to sit between them, right?”

“Maybe I’ll watch it with them, or maybe just bundle them up in blankets and seal them in with duct tape. By the way, I read his script while he was having his interview at Yale, and I thought it was great.”

“Be sure and look in on them several times,” she said. “After all, he is your son, so he got half his genes from you.”

“And the other half from you.”

“That doesn’t make me feel any better.”

“Peter and I had the conversation about sex, you know. I told you about it.”

“Well, I hope you didn’t tell him anything he didn’t already know.”

“I don’t think I did. In fact, about the only thing I could have told him was the only thing I’ve ever really learned about women.”

“Which is?”

“That they like sex just as much as men.”

“Good God! I hope you didn’t tell him that!”

“He’ll find out for himself in due course.”

“Due course is why he needs watching.”

“What would you do, if you were here?”

“I told you: sit between them.”

“I don’t think that’s a possibility,” Stone said. “Anything else?”

“Who is this girl?”

“Hattie something. She lives at Park and Sixty-third.”

“At least she’s from a good address. That makes me sound like a snob, doesn’t it?”

“Everybody at Knickerbocker is from a good address.”

“You know, I think this is Peter’s first real date,” she said.

“Unless something happened at Herald that you don’t know about.”

“Perish the thought! Anyway, they were watched like hawks by the faculty anytime there were girls on campus.”

“Oh, I forgot to tell you: the woman from the Post called again.”

“Prunie?”

“No, the younger one. Joan told her you were doing a book and that you would have nothing further to say until it’s published. Joan thinks that put her off.”

&nb

sp; “I’m so glad. That sort of thing was a constant threat when Vance was alive. We had to book at Beverly Hills restaurants under false names to avoid the paparazzi.”

“New York is better about that, I think.”

“Then why are they so interested in us?”

“Maybe we should hire a publicist,” Stone suggested.

“But we don’t want any publicity.”

“I mean hire a publicist to keep our names out of the columns.”

“How does that work? It sounds unnatural.”

“The publicist puts out a press release saying that he’s representing us, so all the calls go to him, if there’s a question, and he gives them something innocuous, or just brushes them off.”

“Vance never had a publicist.”

“He had the studio, and they have a whole publicity department.”

“You’re right.”

“If we were in L.A. they could handle it for us, but they’re probably too far away. But things have been quiet, since Joan brushed the woman off, so we probably don’t need to do anything about publicity, until Peter is a famous director.”

“Then he can get his own publicist. Oh, a delivery truck has just pulled up outside; I have to go. I love you!”

“Wait a minute!”

“Yes?”

“How did it go with Timothy Rutledge?”

“I managed very well, thank you. Bye-bye!”

“I love you, too,” Stone said, but she had hung up.

Peter arrived at the Brasserie ten minutes early, was given a booth with a view of the front door, and sat down and waited nervously. Hattie was ten minutes late, and Peter had already had a glass of iced tea and needed to go to the bathroom.

He went to meet her as she descended the stairs from the door and escorted her to their booth.

“I really liked your film,” she said, as she slid into her side of the table, “and I already have some ideas about what the score could sound like.”

“Wonderful!” he said.

“Do you have a piano at your house?”

“Yes, but I’m not sure it’s in tune. That’s all right, though, I have an electronic keyboard.”

“Do you play?”

Beverly Hills Dead

Beverly Hills Dead Shakeup

Shakeup Hush-Hush

Hush-Hush Wild Card

Wild Card A Delicate Touch

A Delicate Touch Dead Eyes

Dead Eyes Stealth

Stealth Loitering With Intent

Loitering With Intent Grass Roots

Grass Roots Scandalous Behavior

Scandalous Behavior L.A. Times

L.A. Times L.A. Dead

L.A. Dead Class Act

Class Act Dirty Work sb-9

Dirty Work sb-9 Bombshell

Bombshell Standup Guy

Standup Guy Quick & Dirty

Quick & Dirty Stuart Woods Holly Barker Collection

Stuart Woods Holly Barker Collection Standup Guy (Stone Barrington)

Standup Guy (Stone Barrington) Capital Crimes

Capital Crimes Kisser

Kisser Hot Pursuit

Hot Pursuit Choke

Choke Blue Water, Green Skipper: A Memoir of Sailing Alone Across the Atlantic

Blue Water, Green Skipper: A Memoir of Sailing Alone Across the Atlantic Under the Lake

Under the Lake Unnatural acts sb-23

Unnatural acts sb-23 Doing Hard Time

Doing Hard Time White Cargo

White Cargo The Prince of Beverly Hills

The Prince of Beverly Hills Severe Clear

Severe Clear Bel_Air Dead

Bel_Air Dead Severe Clear sb-24

Severe Clear sb-24 Unnatural Acts

Unnatural Acts Dirt

Dirt Foreign Affairs

Foreign Affairs Unbound

Unbound Family Jewels

Family Jewels Foreign Affairs (A Stone Barrington Novel)

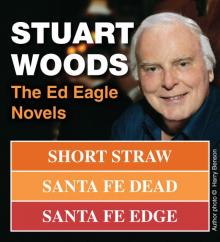

Foreign Affairs (A Stone Barrington Novel) The Ed Eagle Novels

The Ed Eagle Novels Dirty Work

Dirty Work Fast and Loose

Fast and Loose Worst Fears Realized

Worst Fears Realized D.C. Dead

D.C. Dead Deep Lie

Deep Lie Santa Fe Edge

Santa Fe Edge Bel-Air dead sb-20

Bel-Air dead sb-20 The Short Forever

The Short Forever Run Before the Wind

Run Before the Wind Dark Harbor

Dark Harbor Shoot First (A Stone Barrington Novel)

Shoot First (A Stone Barrington Novel) Sex, Lies & Serious Money

Sex, Lies & Serious Money Santa Fe Dead 03

Santa Fe Dead 03 D.C. Dead sb-22

D.C. Dead sb-22 Swimming to Catalina

Swimming to Catalina Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage Hot Mahogany

Hot Mahogany Barely Legal

Barely Legal Imperfect Strangers

Imperfect Strangers Paris Match

Paris Match Mounting Fears

Mounting Fears Mounting Fears wl-7

Mounting Fears wl-7 Shoot Him If He Runs

Shoot Him If He Runs Short Straw

Short Straw Santa Fe Dead

Santa Fe Dead Dead in the Water

Dead in the Water Hothouse Orchid

Hothouse Orchid Below the Belt

Below the Belt Orchid Beach hb-1

Orchid Beach hb-1 Son of Stone sb-21

Son of Stone sb-21 Cold Paradise 07

Cold Paradise 07 Blood Orchid

Blood Orchid Fresh Disasters

Fresh Disasters Lucid Intervals

Lucid Intervals Dishonorable Intentions

Dishonorable Intentions Cut and Thrust

Cut and Thrust The Money Shot

The Money Shot Santa Fe Rules

Santa Fe Rules Iron Orchid

Iron Orchid New York Dead

New York Dead The Short Forever sb-8

The Short Forever sb-8 Son of Stone

Son of Stone Insatiable Appetites

Insatiable Appetites Chiefs

Chiefs Unintended Consequences

Unintended Consequences Reckless Abandon

Reckless Abandon Three Stone Barrington Adventures

Three Stone Barrington Adventures Stuart Woods 6 Stone Barrington Novels

Stuart Woods 6 Stone Barrington Novels Shoot First

Shoot First Indecent Exposure

Indecent Exposure The Run

The Run Bel-Air Dead

Bel-Air Dead Strategic Moves

Strategic Moves Cold Paradise

Cold Paradise