- Home

- Stuart Woods

The Run Page 2

The Run Read online

Page 2

“Neither have we.” Adams nodded at the waiter. “Tell Carlos what you’d like.”

“An egg white omelet, dry toast, and coffee,” Kate said.

“Scrambled eggs and smoked salmon, home fries, English muffin, and more orange juice,” Will said, ignoring a sharp glance from his wife. “Coffee later.”

The Adamses ordered, then joined Will and Kate before the fire. “I love this place in winter,” Adams said, “and the president was kind enough to offer us the lodge. Where is Peter? I thought he’d be with you.”

“It’s his dad’s turn to have him for Christmas,” Kate said of her son. “He’s going to Boston.”

“And how old is he now?”

“Sixteen. A sophomore at Choate, his father’s school.”

“I know you’re proud of him.”

“I certainly am. He’s doing very well in school; sports, too. Where are your children, Mr. Vice President?”

“It’s Joe and Sue, please,” Adams said. “They’re already at my folks’ place in Florida. We’re flying down to join them this afternoon.”

“How was New York?” Will asked. The vice president’s trip had been in the news—he’d made some speeches while his wife Christmas shopped.

“Just lovely this time of the year,” Adams replied. “We got to the theater a couple of times. It was almost a vacation.”

“Have you got your shopping all done, Kate?” Sue Adams asked.

“I’m relieved to say I have,” Kate replied. “We sent Peter’s gifts to Boston earlier in the week, and I found a very nice lump of coal for my husband.”

The Adamses laughed, then the food arrived, and everyone dug in, keeping up an animated conversation. Will knew Joe Adams very well—Adams had been the first senator to befriend him as an equal, when Will had arrived on the Hill as a senator, instead of as a senatorial aide, and he had known him through committee work before that. While their conversation was the chat of good friends, Will thought he caught something strained in Adams’s behavior, and in his wife’s, too.

Finally, the dishes were cleared away, and a pot of coffee was set on the table. Sue Adams poured for everyone, then sat down. There was a moment of complete silence, then the butler came back.

“Would you and your guests like anything else at all, Mr. Vice President?” he asked.

“Thank you, Carlos, no. Would you tell the Secret Service man at the door and your own staff that we don’t wish to be disturbed for a while?”

“Of course, Mr. Vice President.” Carlos bowed and left the room.

The silence came back. Will waited for someone to break it.

Joe Adams finally did. “Will, Kate,” he said, “we’ve asked you up here to give you some news personally.” He paused and cleared his throat. Sue Adams stared out a window at the snow.

He’s not going to run, Will thought. Is he insane? The office is his for the taking. Has he had an affair? A stroke? What the hell is going on?

“First of all, I want you to know that this room is not bugged, and our conversation is not being recorded. I had the Secret Service double-check that earlier today. What I’m about to tell you and Kate I intend to tell only you and Kate—you, Will, because, more than anyone else besides Sue, you have a right to know. You’re as close a friend as I have, and you’ve put more into my presidential effort than anyone else. Kate, I want you to know, because I don’t want Will to have to keep this from you. I know that I don’t even have to ask you both to keep this in the strictest confidence.”

Will and Kate nodded. The atmosphere in the room had become somber. Sue Adams got up and went to the window, turning her back to them. She produced a tissue and dabbed at her face.

“Our trip to New York wasn’t just for speeches, the theater, and shopping,” Joe Adams said. “There was another reason.”

Oh, God, Will thought. I don’t know what this is, but I know I’m going to hate it.

Joe Adams took out a handkerchief, blew his nose, returned the handkerchief to his pocket, then continued.

3

The vice president took a sip of his coffee and began to speak. “The week before last I had my annual physical at Walter Reed Hospital. It went beautifully, and I got a clean bill of health. Ironically, it was the first time I can remember when everything—weight, cholesterol, blood pressure, the works—was right on the money.” He took another sip of his coffee. “But I wasn’t entirely frank with the staff at Walter Reed.”

Will shifted uncomfortably in his seat. If his friend had a clean bill of health from Walter Reed, what the hell could be the matter?

“There was something they didn’t pick up on at the hospital,” Joe Adams said, “something they wouldn’t have detected unless they had been looking for and tested for it specifically. I’d had some symptoms that only Sue and I knew about; that’s why we arranged the New York trip. My old college roommate is now one of the two or three top neurologists in the country, and he put together a very thorough series of tests, some of them quite new. Those things that had to be accomplished at a hospital were done in the middle of the night, and under an assumed name, with a minimum of trusted staff present. The other tests were conducted in a suite at the Waldorf Towers, adjacent to our own quarters. The results of all this testing, by the top experts in the field, were conclusive.” He looked at Kate, then back at Will. “I’m in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease.”

Will had been holding his breath; he let it out in a rush. “Joe…” he began.

Adams held up a hand. “Please; let me tell you everything. I know your first question will be, shouldn’t I get a second opinion. My testing encompassed three opinions, independently arrived at. They were all in complete agreement. I have it; it’s going to get worse; and, unless I get lucky and have a coronary, I’m eventually going to die from it.”

Sue Adams returned from the window and took her seat. Her eyes were red.

Kate put her hand on Sue’s.

“Joe and I have a hard road ahead of us,” Sue Adams said, “and we’re going to need your help.”

Adams continued. “Your next question is going to be, I know, will I resign? The answer is no, and I’ll tell you why. I talked with the president yesterday, before he left for California, and I told him I was thinking of resigning my office in order to pursue my presidential campaign full-time. He neither encouraged nor discouraged that action. As you know, he hasn’t made any promise to support my candidacy. We weren’t the best of friends or the closest of colleagues before we were elected—he picked me as his running mate for purely pragmatic reasons—and we’ve disagreed as often as we’ve agreed on issues. So I asked him, frankly, who he would appoint as my successor if I resigned.”

Given what he had heard so far, Will was very anxious to hear the president’s answer to this question.

“To my surprise,” Adams continued, “the president told me he had anticipated my thoughts about resigning. He knew that not being vice president would allow me to disagree with his policies more often. As a result, he said he had given a lot of consideration to whom he might appoint. I half expected him to ask for my recommendation, and I was going to recommend you, Will.”

“Why thank you, Joe,” Will managed to say.

“But he didn’t ask. Instead he told me he had decided not to appoint a new vice president. He’s under no constitutional obligation to do so, of course, and he said that, with barely more than a year left to serve, he thought that the speculation surrounding the appointment and the jockeying for advantage by various groups would create too much distraction from the important issues he wants to resolve before he leaves office. As it happens, I think he’s right, but if I resigned, his failure to appoint a successor would leave us with an unacceptable situation: It would put the Speaker of the House in line to succeed the president, if he should die before his term ends.”

Will nodded his understanding.

“Now, I’ve always made a great effort to have good relations with the

Speaker, and I’ve tried to consider his position on various issues, but I have to tell you that his positions are so bizarre, sometimes, and always so self-serving and partisan, at the expense of the country, that I swear, if he became president, I’d have to shoot him myself.”

Will and Kate both laughed.

“But rather than entertain that possibility,” the vice president continued, “it seemed simpler just not to resign my office and continue to campaign for the presidency as vice president.”

Will blinked. “Continue to campaign?” he asked incredulously.

Adams held up a hand. “Easy, Will; I’m not crazy yet. In my condition, I’d never try to be elected president. There’ll come a right moment to leave the race, and when it happens, I’ll recognize it, but it’s not now. The best medical advice I can get is that the progress of my disease will be slow, and that there’s no reason why I shouldn’t serve out my term. I’d like to do that, especially because I know now that I can never be president. I think that I can have a positive influence on events and, particularly, on the next session of Congress, if I remain in office.”

Will conceded to himself that that was so.

“However, I don’t want my medical condition to become public knowledge as long as I can lead a fairly normal life. That would keep me from having any influence on events, and I don’t want that while I can be a positive force in national affairs. I announced for the presidency early on, in order to discourage some other potential candidates, and if I withdraw now, I’ll have to explain why, and I can’t think of an explanation that would ring true. I’d have the press all over me, probing into my life for the real reason, and eventually they’d find it.”

“That’s true enough,” Will said.

“So I plan to continue as if nothing were wrong,” Adams said. “I’ll do my job as vice president, I’ll do the minimum necessary in the way of campaign appearances, and I’ll continue to raise money.”

“Joe,” Will said, “that troubles me, because when you finally do withdraw from the race it will be apparent that you will have been accepting campaign donations under what amounts to false pretenses. I don’t think you can do that.”

“I’ve already addressed that problem,” Adams said. “What I plan to do is to make an offer to every campaign contributor at the time of my withdrawal. I’ll give them a choice: I’ll refund their donation; I’ll direct it to the campaign of any candidate they designate; or I’ll turn it over to the Democratic Party. I’ll mail a form to every contributor that they can fill out, sign, and return, and I’ll act on those wishes.”

“Have you given any thought as to when you might withdraw?”

“Early on, but after the Iowa caucuses and the earliest primaries, like New Hampshire.”

Will nodded. “Are you sure you’re doing the right thing, Joe?”

“No, I’m not. I’m just making the best decision I can in the circumstances. If I announce my condition and resign now, then all I can do is go home to Florida, sit on the beach, and wait to go crazy and die. If I stay on, I can have some real influence on the president’s legislative program and on next year’s congressional elections. The Republican majority in both houses is razor-thin, and I want to win back both the Senate and the House, as well as a great many governorships. If I’m out of office, I’ll leave a vacuum, and I don’t want that.”

“I can understand your position, Joe,” Will said.

“Sue supports me in this,” Adams said. “She’s always been my closest advisor, and she’s going to stick close to me to be sure that I don’t do the wrong thing because of a memory lapse—which, by the way, is my principal symptom so far—short-term memory loss. I’d like to stress that I am not delusional. I plan to deal with my memory lapses by having notes taken at every opportunity, so that nothing will get by me. I’ll depend a lot on Sue for that.”

“That’s a good idea,” Will said.

“There’s something else, Will,” Adams said. “When I withdraw, I’m going to do so in your favor. I’m going to ask my contributors to assign their contributions to your campaign.”

Will had not yet given any thought to his own position, and he was stunned. “That’s incredibly generous of you, Joe,” he managed to say. “But Kate and I are going to have to talk about this.”

“Of course you will,” Adams replied. “Fortunately, you have the holidays ahead of you, and there’ll be time before you announce.”

“Announce?” Will said.

“I want you to announce for the presidency right after New Year’s; I want you to have established yourself as a candidate independent of me in the minds of the electorate before I withdraw.”

“I’ll have to give that a lot of thought, Joe.”

Sue Adams spoke up. “Will, speaking for myself, I think you’re now the Democrat who is best qualified for the presidency. You’re well established at the center, as well as at the heart of the party, and Joe and I want to see you elected next November.”

“We certainly do,” Adams said. “You are superbly qualified by temperament, training, and intellect. As far as I’m concerned, nobody in either party comes close.”

Will warmed to the praise, but he was being sucked into this little conspiracy, and he wasn’t entirely comfortable with it.

Adams seemed to sense his disquiet. “Will, all I’m asking you to do is to help me make a graceful exit from public life, while accomplishing as much as I can in the time remaining to me. Is that too much to ask of a close friend?”

“No, certainly not,” Will replied.

“Good,” Adams said. “Call me when you’ve made a decision about announcing.”

4

Will took off from College Park Airport and called Washington Center for his clearance, as the Marine lieutenant had instructed him to do. To his surprise, he was cleared direct to his home airport in Warm Springs, Georgia, instead of being routed on airways. He climbed to his assigned altitude of 18,000 feet, leaned the engine, punched the identifier for Warm Springs into his GPS computer, switched on the autopilot, and sat back, doing an instrument scan every minute or so.

Hardly a word had passed between him and Kate on the helicopter ride back to College Park, and until now, he had been too busy flying to talk. He wanted to talk.

“This whole thing scares me to death,” Will said.

“You? Scared of running for president?”

“Not that, so much; it’s Joe’s situation. It’s like a bomb that may or may not go off.”

“Do you really think he’s doing the right thing?”

Will shrugged. “I’m not sure there’s only one right thing,” he said. “It would be right if he announced his condition publicly and resigned, but who’s to say that what he’s doing is wrong? He has some very good points about his usefulness to the party and the country over the next months. I certainly wouldn’t deny him that.”

“You understand that, if the bomb goes off, it’s going to hurt you, as well as Joe.”

“Maybe; that’s entirely unpredictable. I’ve been thinking back over the history of the presidency, and the only thing I can think of that resembles this situation is Woodrow Wilson’s illness in office, and his wife’s acting for him. Of course, it’s not quite the same thing; Joe’s not president. If he were, I think he’d have to resign, regardless of the consequences.”

“Do you think Reagan was in the early stages of Alzheimer’s during his last term?”

“I don’t know; it’s possible, I guess, and it’s also possible that nobody really noticed. After all, he was the oldest president, and you’d expect some slowing down at that age.”

“Remember when he had to testify in court? He said ‘I don’t recall’ dozens of times. At the time I thought he was dissembling, but maybe he really didn’t remember.”

“Maybe not.”

Kate was quiet for a while, then she spoke. “If you do this, it’s going to play hell with our lives.”

“That’s true of everybo

dy who ever ran for the office,” Will replied. “Do you not want me to do it?”

“Oh, Will, I think you’d make a superb president, you know that.”

“I’m glad you think so. What we have to get clear between us is what your role is going to be.”

“What do you want my role to be?”

“We have two choices, I think: One is that you resign from the Agency and play the campaign wife. I know you don’t want to do that, and I don’t expect you to. The other is for you to remain at the Agency and do your job. I can say, in campaigning, that my wife and I are both public servants and that we decided, together, that the country would be best served by your remaining at the Agency.”

“Sounds good to me,” Kate said.

“Understand, though, that there are times when I’ll want you at my side: at the convention, for instance, and, if I get the nomination, on election night.”

“At the whole convention, or just for the smiling and waving at the end?”

“At the whole convention, I think. There has to be some time when the party and the press get to feel that you’re a real person and not just a cardboard cutout that’s set up for photo ops.”

“All right, I can take vacation time for the convention.”

“Also, when I make evening appearances in or around Washington, I’d like you on the platform, work permitting.”

“Work permitting, okay. What about Peter?”

“The last night of the convention and election night only; that’s all I’ll ask of him. I don’t want to interfere with his schooling or with his relationship with his father.”

“Yes, that would really set Simon off.”

“I don’t want you to press Peter to do this; I’d rather not have him there than have him think I’m imposing on our relationship.”

“Peter loves you, Will; you know that. He’ll be glad to help.”

“You’re going to have to warn him about the press, too, and…” Will stopped.

“Tell him to stay out of trouble?”

Beverly Hills Dead

Beverly Hills Dead Shakeup

Shakeup Hush-Hush

Hush-Hush Wild Card

Wild Card A Delicate Touch

A Delicate Touch Dead Eyes

Dead Eyes Stealth

Stealth Loitering With Intent

Loitering With Intent Grass Roots

Grass Roots Scandalous Behavior

Scandalous Behavior L.A. Times

L.A. Times L.A. Dead

L.A. Dead Class Act

Class Act Dirty Work sb-9

Dirty Work sb-9 Bombshell

Bombshell Standup Guy

Standup Guy Quick & Dirty

Quick & Dirty Stuart Woods Holly Barker Collection

Stuart Woods Holly Barker Collection Standup Guy (Stone Barrington)

Standup Guy (Stone Barrington) Capital Crimes

Capital Crimes Kisser

Kisser Hot Pursuit

Hot Pursuit Choke

Choke Blue Water, Green Skipper: A Memoir of Sailing Alone Across the Atlantic

Blue Water, Green Skipper: A Memoir of Sailing Alone Across the Atlantic Under the Lake

Under the Lake Unnatural acts sb-23

Unnatural acts sb-23 Doing Hard Time

Doing Hard Time White Cargo

White Cargo The Prince of Beverly Hills

The Prince of Beverly Hills Severe Clear

Severe Clear Bel_Air Dead

Bel_Air Dead Severe Clear sb-24

Severe Clear sb-24 Unnatural Acts

Unnatural Acts Dirt

Dirt Foreign Affairs

Foreign Affairs Unbound

Unbound Family Jewels

Family Jewels Foreign Affairs (A Stone Barrington Novel)

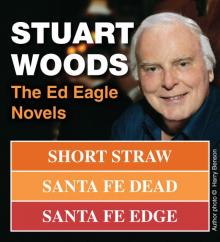

Foreign Affairs (A Stone Barrington Novel) The Ed Eagle Novels

The Ed Eagle Novels Dirty Work

Dirty Work Fast and Loose

Fast and Loose Worst Fears Realized

Worst Fears Realized D.C. Dead

D.C. Dead Deep Lie

Deep Lie Santa Fe Edge

Santa Fe Edge Bel-Air dead sb-20

Bel-Air dead sb-20 The Short Forever

The Short Forever Run Before the Wind

Run Before the Wind Dark Harbor

Dark Harbor Shoot First (A Stone Barrington Novel)

Shoot First (A Stone Barrington Novel) Sex, Lies & Serious Money

Sex, Lies & Serious Money Santa Fe Dead 03

Santa Fe Dead 03 D.C. Dead sb-22

D.C. Dead sb-22 Swimming to Catalina

Swimming to Catalina Collateral Damage

Collateral Damage Hot Mahogany

Hot Mahogany Barely Legal

Barely Legal Imperfect Strangers

Imperfect Strangers Paris Match

Paris Match Mounting Fears

Mounting Fears Mounting Fears wl-7

Mounting Fears wl-7 Shoot Him If He Runs

Shoot Him If He Runs Short Straw

Short Straw Santa Fe Dead

Santa Fe Dead Dead in the Water

Dead in the Water Hothouse Orchid

Hothouse Orchid Below the Belt

Below the Belt Orchid Beach hb-1

Orchid Beach hb-1 Son of Stone sb-21

Son of Stone sb-21 Cold Paradise 07

Cold Paradise 07 Blood Orchid

Blood Orchid Fresh Disasters

Fresh Disasters Lucid Intervals

Lucid Intervals Dishonorable Intentions

Dishonorable Intentions Cut and Thrust

Cut and Thrust The Money Shot

The Money Shot Santa Fe Rules

Santa Fe Rules Iron Orchid

Iron Orchid New York Dead

New York Dead The Short Forever sb-8

The Short Forever sb-8 Son of Stone

Son of Stone Insatiable Appetites

Insatiable Appetites Chiefs

Chiefs Unintended Consequences

Unintended Consequences Reckless Abandon

Reckless Abandon Three Stone Barrington Adventures

Three Stone Barrington Adventures Stuart Woods 6 Stone Barrington Novels

Stuart Woods 6 Stone Barrington Novels Shoot First

Shoot First Indecent Exposure

Indecent Exposure The Run

The Run Bel-Air Dead

Bel-Air Dead Strategic Moves

Strategic Moves Cold Paradise

Cold Paradise